A Portrait for Today

What will the soundtrack of 2020 be like? What will its poetry say? How will artists capture all that’s happening? Right now, they’re at their desks, with their instruments, and in their studios, responding, reacting and reaching. At some point, we’ll find out what art thought of this surprising, unprecedented moment and see how artists found ways to make these days more relatable and relevant. More human.

Art has touched the human soul for as long as there has been art; that’s why we thrill to see a hand that was painted on a cave wall more than 50,000 years ago. Immediately it connects, telling us others have been here, and we are not alone. That connection can be elusive, subtle, or come straight at you. One image that seems to speak so well and clearly to this moment was painted a half century ago. It’s Alice Neel’s portrait of Andy Warhol, a masterpiece at the Whitney Museum.

Neel (1900-1984) was an acclaimed New York artist who painted her truth – the people around her – for decades, while others were busy upending the cultural landscape with abstraction. She was born to a working class family in Pennsylvania and took a clerical job after high school to help make ends meet, while taking night classes in art. Neel reported that her mother once told her, “I don’t know what you expect to do in the world, you’re only a girl.” She went on to become the 20th century’s greatest American portraitist, compared by art historians to Vincent van Gogh.

Forever focused on figures and faces, Neel was largely left behind by an art world that had turned away from realism during the 1940s and 50s, but she was known and admired by other artists. She became widely appreciated in the late 1960s, thanks, in part, to the feminist movement, and galleries and museums began to collect her work.

Neel, meanwhile, was busy collecting souls, as she so aptly described her paintings. For her subjects she chose friends, lovers, kids from the neighborhood (she lived in upper Manhattan for five decades, first in Spanish Harlem, and later on the Upper West Side) and sometimes other artists and celebrities, including Marisol, Robert Smithson, Ed Koch and Bella Abzug.

Scars and Stitches

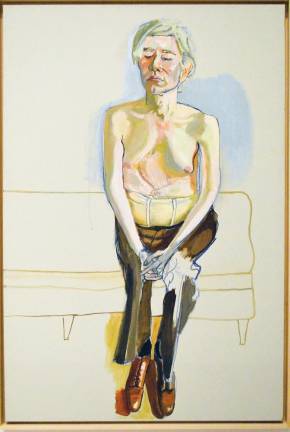

In 1970, she painted Andy Warhol. Two years earlier, Warhol had survived an assassination attempt, when Valerie Solanus, part of his artistic circle, shot him three times. Neel painted Warhol’s scars and stitches, and the girdle he wore to support his damaged muscles. In her painting, Warhol’s flesh is tinged in green. His eyes are closed. His hair is gray. He looks old and tired. His shoulders, outlined in ultramarine blue, are thin. Nowhere is the flamboyant, wig-wearing, Pop icon, star artist. Instead, we see a man, stripped of pretense, baring himself, his eyes closed in a kind of psychic self-protection.

He sits on a brown couch, or the suggestion of one. Only its outlines are provided. All the focus is on Warhol’s face and flesh, their tones offset by a heavenly sky blue. It’s monumental, yet at a scale we can approach. There’s nothing else there – no background, no furniture, no window to hint at time of day or year. Neel acknowledged the picture’s intentionally “hypersensitive economy.” Alone and defenseless, Warhol, who thrived in society and embraced artifice, is transformed. He becomes touchingly human.

Would it be a stretch to see in the two main elements – a bare, vertical figure against brown horizontal lines – echoes of the countless crucifixion scenes that have been painted? Is the message so different? Both confront mortality, even as they telegraph hope. Both touch on themes of humanity – trials, suffering, survival and transcendence. Or, as Neel put it, picturing people in terms of “what the world has done to them and their retaliation.”

Like all except self-portraits, this portrait reveals two individuals, both the sitter and the painter. Through Warhol’s poignant fragility, we see the tenderness and kindness of Alice Neel’s gaze. It was hard-earned. Neel suffered tragedies in her own life, living through periods of abandonment, depression, poverty, and loss.

Here, she shows us an imperfect person living in an imperfect world. All affectation has been removed, and what remains is arrestingly, stop-you-in-your-tracks beautiful. Alice Neel’s “Andy Warhol” is more than a portrait. It’s a vision of vulnerability, humanity and deep, resonant empathy. It’s been a powerful statement for fifty years, but it’s never been more relevant.

Like all except self-portraits, this portrait reveals two individuals, both the sitter and the painter. Through Warhol’s poignant fragility, we see the tenderness and kindness of Alice Neel’s gaze.