beauty, tension and mapplethorpe

Loves, lusts, lives and losses inform the creative drive. Authentic artists have no choice but to depict their reality, and realities vary in time and place. Renaissance Florence produced pious perfection. Amsterdam’s Golden Age engendered an earthy elegance. In downtown Manhattan in the 1970s, the sizzle of the streets gave off a kind of gritty glory that inspired new kinds of art.

Robert Mapplethorpe captured moments within that world with technical mastery and unapologetic frankness. The Guggenheim Museum’s “Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now” presents some 80 works in an effort to reintroduce him to a new generation of artists and audiences. It’s the first installment of a two-part, year-long celebration of Mapplethorpe’s life and legacy, and of a 1993 gift from the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation that transformed the museum’s photography collection and aspirations. In July, the second part will feature artists influenced by Mapplethorpe alongside more of his own works.

“At the time of his death from AIDS-related complications in 1989, it was already acknowledged he was one of the most pivotal photographers of his generation,” noted co-curator, Lauren Hinkson. “Mapplethorpe the cultural icon is such a powerful figure that it’s important to rediscover what Mapplethorpe the artist accomplished.”

His achievements are on view in photographs and collages that range from early, experimental works to mature mastery of his medium. Born in Queens in 1946, Mapplethorpe came of age when sex, drugs and rock and roll were an anthem and a rallying cry. At age 42, he passed away. His short career was noted for originality and candor as well as the reactions, retribution and censorship triggered by his work that continued beyond his life.

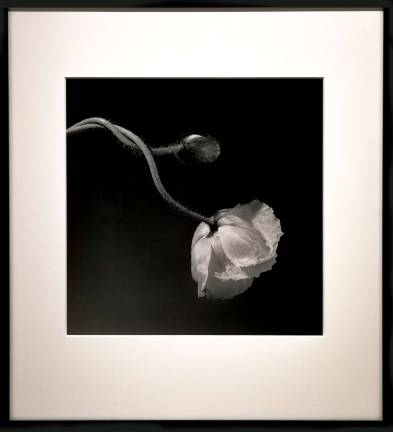

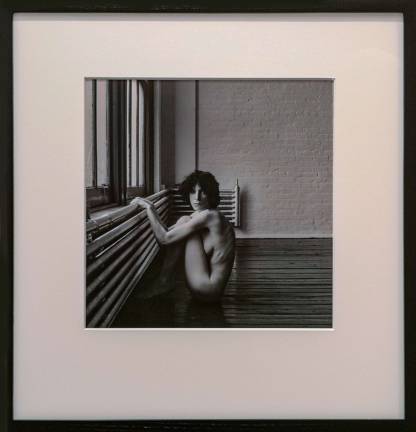

The photographs include portraits of celebrities, sensual nudes, crisp still-lifes, erotic explorations and floral images. Most are in black and white. All are marked by a sensitivity to poise and a reach for beauty, regardless of subject matter.

Organized by Hinkson and Susan Thompson, with Levi Prombaum, curatorial assistant, the exhibition presents thoughtful groupings and arrangements creating conversations between subjects, many of them musicians, artists, and writers. Particularly touching is a dreamy portrait of Alice Neel, the artist softened and vulnerable in her old age, alongside a self-sure, potent Louise Bourgeois, about the same age, archly smiling. In a deft curatorial touch, a hallway arrangement starts with a shooting gun and a horned, devilish Mapplethorpe self-portrait, hinting at the more explicit images that await just beyond them.

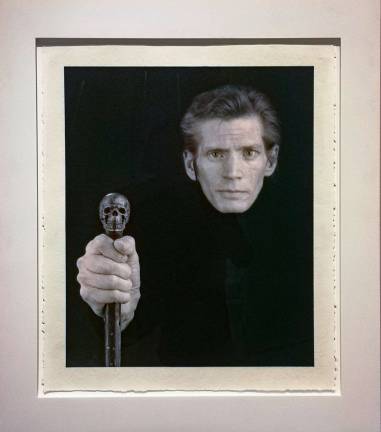

Among the highlights are Mapplethorpe’s self-portraits. Like those done by Rembrandt or Van Gogh, they’re genuine — not about gloss and surface, but about questions, declarations, self-knowing, identity, exploration, and ultimately, mortality.

“Self-Portrait,” 1988, done shortly before his death, is a poignant, arresting visual and conceptual statement. Dressed all in black, Mapplethorpe sits against a dark background. His face hovers, disembodied. It is composed, intense, gaunt but almost hinting at a smile. In the foreground, he holds, in a strong grip, a cane topped by a carved skull. Near and far, flesh and bone, acceptance and defiance all come together for a moving memento mori. How many artists have depicted themselves with such honesty and bravery?

“I’m looking for perfections in form,” Mapplethorpe once said. Hinkson shared her thoughts on the push and pull between the technical beauty and controversial imagery in Mapplethorpe’s work. “When Robert was working there was always complete control of what was taking place within the image whether it was light or shadow, what people were wearing, where they’re positioned. And that’s all in service of this search for perfection of form and seeking out a way to communicate beauty and raise whatever the image is to an art form,” she said. “I think you’re drawn in by the beauty of the images and then you’re pushed away sometimes by the content and then you get pulled back in again by that tension. That’s one of the reasons why we used tension in the title, because there’s conflict and tension between content and images and the way they are produced.”