Native american art, and stories

There are many stories in the Metropolitan Museum’s “Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection.” One of them is the story of the exhibition’s location. For the first time, New York’s great encyclopedic museum is exhibiting Native American work in the American Wing. Previously, it’s been shown in the galleries for Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

“The presentation in the American Wing of these exceptional works by indigenous artists marks a critical moment in which conventional narratives of history are being expanded to acknowledge and celebrate the contributions of cultures that have long been marginalized,” stated Max Hollein, the museum’s director. The Dikers, whose collection of Native American works of art is deep and exquisite, donated 91 of the 116 works on view. They did so with the stipulation that the works be placed within the context and galleries of American art, to reflect the work’s place in our culture. It’s an important, inclusive move for a multicultural society’s flagship museum, reversing decades of conceptual and artistic separation.

But that’s just one of the stories here. The others are within the works themselves, in the voices they carry and the lives they represent. They’ve been collected from some 50 cultures across North America and include masks and implements from the Northwest Coast, basketry from California, drawings and clothing from Plains peoples, pottery from the Southwest, and carvings and ornamental dress from the eastern Woodlands cultures. Artists from the 2nd to the 20th centuries created these humble, powerful, sacred and quotidian objects that transcend time and place, and speak to personal and universal truths.

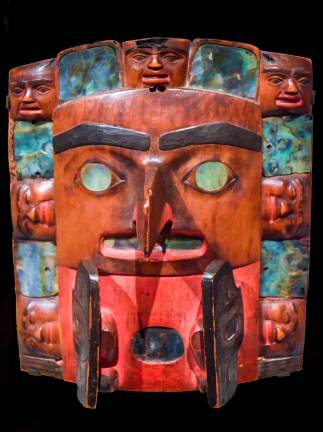

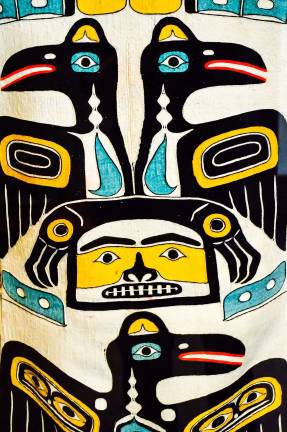

Northwest Coast and Arctic cultures were blessed with plentiful fishing and hunting. They settled in communities and created stunning, abstract images of the natural world around them, decorating spoons and spears, boats, buildings and masks that opened portals of spiritual communication. Ancestors and animal guides were invoked in rituals to heal, bless, teach and protect. Shamanic performances were enhanced by elaborate theatrical masks with moving parts. To see the layers of imagery in a Yup‘ik artist’s mask from Alaska (c. 1900) with a bent branch representing the borders of the universe, a kayak filled with images of seals, birds and fish surrounded by reaching hands, is to feel the power of the hunt. To picture these parts shaking as a dancer moved in flickering firelight is to conjure a sublime experience.

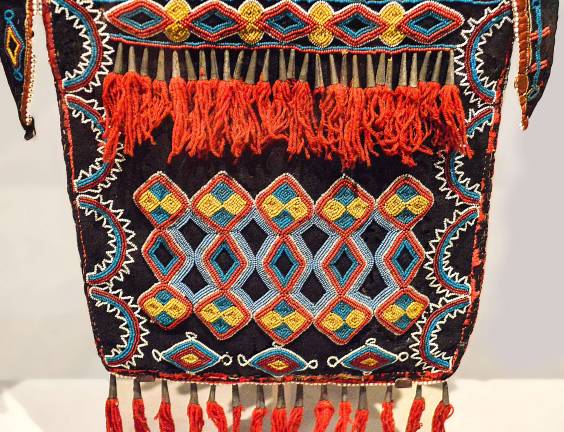

Stories can be found in the materials utilized as well. Forests provided wood for Northwest Coast and Eastern Woodlands communities. Nomadic hunting peoples of the Plains and Plateau regions made spectacular domiciles, drums, garments, and accoutrements from leather. A cradleboard to welcome and protect a new member of the Ute community in Colorado or Utah around 1890 was like a stiff-walled backpack. It could be worn by a mother on horseback or propped against the sloping walls of a tipi. A hood of thin wooden rods that shielded the baby’s eyes from the sun also functioned as an awning, protecting her face if the cradleboard tipped forwards. The attention to functional details attests to the care expressed by these artists for the newborn; the extraordinary beauty of the buttery yellow background, decorated with bright curvilinear forms and intricate beadwork, speaks of their joy in new life.

Another story comes through in beadwork. An Anishinaabe shoulder bag from 1780 is decorated with dyed, flattened woven porcupine quills. A Nez Perce War Shirt, circa 1850, made use of both quills and glass beads, which, by then, had been made available through trading with settlers. Ledger drawings made by Plains artists around the 1860s present complex histories and imagery. With pencils and sheets of paper from ledger books, often captured from the U.S. military, these artists depicted their victories on their adversary’s own materials.

From stunning monochromatic abstraction on pottery from pueblos in New Mexico, created over a thousand years ago, to baskets made by the 20th century master Louisa Keyser, known also as Datsolalee, the works in the show tell stories that are ancient, recent and evolving.

“Our ancestors must have had an inner strength. As Native peoples seemed to reach the nadir of their existence, they did not die off or disappear into the larger American society. Instead, they experienced a renewed sense of creativity,” states a wall text by Emma I. Hansen, a Pawnee scholar and curator. “Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection” is a quiet blockbuster that challenges and changes history by presenting vividly voiced works by great American artists, whether known and documented or lost to history.