vital signs

The 2019 Whitney Biennial is beautiful. It’s not the most provocative, radical, assertive, or declarative Biennial in memory, but it’s stunning. It’s got an open, airy feel, and is filled with vibrant, compelling works that invite the viewer into conversations without imposing themselves. That’s not to say it’s not serious, challenging and of the moment. It is. It’s diverse and engaging, comprised of works largely by women and artists of varied experiences and viewpoints, ethnicities, sexual orientations, and physical abilities.

Sevnty-five artists are presented, for the most part clustered into groups of three to four works per artist. Set up as kind of mini-solo shows, they give a sense of the artists’ approaches and voices across bodies of work. It allows for in-depth communication, and gives a sense of what each artist can do. Generous wall texts add explanations and the curators’ interpretations, making them accessible to all.

The State of American Art ... Co-curators Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta traveled the country for 18 months to take its artistic vital signs. Their introductory statement discusses the deep divisions they found, along with artists who are working out “political and aesthetic strategies for survival. Although much of the work presented here is steeped in sociopolitical concerns,” they state, “the cumulative effect is open-ended and hopeful.”

Collage plays a starring role, as do fiber arts, sculptures made of found objects, symbols and things that stand in for languages. Surprisingly, there is not a lot of technology. Rather, Hockley and Panetta state that they encountered a turning away from the digital and a return to the handmade.

One piece that touches both technology and the handcrafted is Nicholas Galanin’s “White Noise, American Prayer Rug.” The Tlingit/Unangax artist’s weaving recalls Chilkat blankets, with dangling wool fringes and rough, textural weave. But here, rather than abstracted spirit figures, there’s a representation of a screen filled with pixilated white noise. Ancient forms joined with oversized screens suggest a change in language, and what’s been lost.

Also referencing language is Gala Porras-Kim’s “La Mojarra Stela illuminated text.” Porras-Kim alludes to colonialism, communication, and the accessibility (or lack thereof) of the past. She paints characters of Epi-Olmec text discovered on a stela in the 1980s that remain undeciphered, yet are prominently displayed in a museum in Mexico. In front of the canvas is a rotating disk meant to recall divination bowls. Mystery embedded in a once expository text makes an interesting statement.

Maia Ruth Lee’s steel glyph, “Labyrinth,” communicates through a language of rusted, disused shapes. It fills one large wall with a kind of visual semiotics and brought to mind the Barnes Foundation’s displays of door hinges and locks alongside modern masterpieces.

And the American Dream Tomashi Jackson’s layered, colorful, elegantly balanced collages sing with a voice I want to hear more from. In “Third Party Transfer and the Making of Central Park,” she’s discussing opportunities in housing through imagery suspended from a sheltering urban awning. Her found objects, shopping bags, texts and images invite with beauty and reward those who enter.

Ilana Harris-Babou presents a trio of videos that riff on corporate advertising while exposing harmful business practices and the deceptive nature of nostalgia. I spoke with her about “Reparation Hardware,” one of about her works.

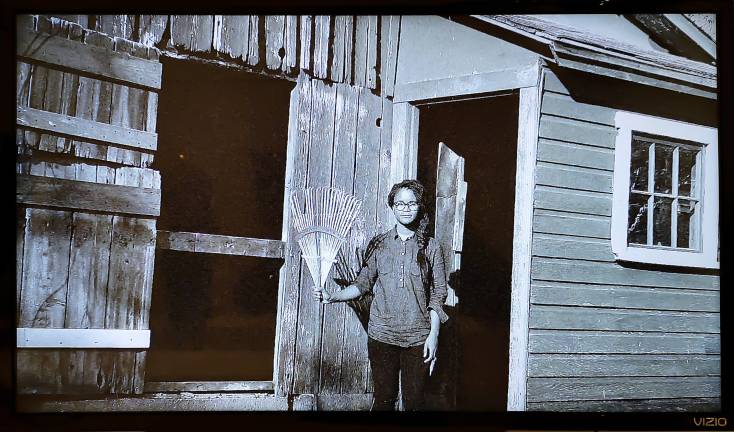

“I’ve been thinking a lot about the American dream and the ways we try to find authenticity or community or absolution by buying nice things,” said Harris-Babou. “For these three videos I’m taking Restoration Hardware, which is a high end furniture design company that has a new big flagship store around the corner from the museum, as a kind of muse or lens through which to think about different aspects of the idea. When they come out with new design lines, they have these promotional videos with the designer maybe in front of a waterfall talking about where he finds inspiration. So I’m that designer but I’m designing reparations for African Americans. It’s about an admission of history being a failure, rather than someone buying an authentic thing from and old farmhouse and saying history is a success. It’s a kind of wanting for the past to be finished or resolved and the comfort that comes along with that. But then there’s a bubbling up of the realization that isn’t true. It’s not resolved.”

A Reflection of Who We AreResolution is far from the theme of this year’s Biennial. Questions, memories, history, hegemony, self-affirmation, probing and protest are among its subjects. From Jeffrey Gibson’s ebullient banners sharing materials and influences from his heritage (Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and Cherokee) to Christine Sun Kim’s series of pastel drawings “Degrees of Deaf Rage in Everyday Situations,” each work has the ability to strike a chord with every viewer. The artists have made their statements. It’s our turn to listen.

In paintings, drawings, videos, sculptures, performance and more, in an exhibition that’s diverse, Intelligent, passionate and compassionate, at times belligerent, but hopeful, the 2019 Whitney Biennial looks a lot like us.