Making Every Word Count for Every Person

Award-winning journalist Maria Hinojosa on her new memoir, the city in the 80s and working the overnight news shift

Growing up on the South Side of Chicago, Maria Hinojosa idolized journalists like Dan Rather and Bill Moyers, never imagining she would become one herself. She did, however, see female journalists in her native Mexico, and thankfully chose to embark on that professional path. Throughout her now-close-to 30-year career, she has been effecting change with her in-depth reporting on subjects such as detention camps, prison and immigration, with a mission to serve communities that tend to be neglected by the mainstream media.

After building an impressive journalistic resume, which includes outlets like NPR, CBS, PBS and CNN, she launched her own media nonprofit, Futuro Media Group, a decade ago. Based in Harlem, the community-based organization reports on stories centered around the theme of diversity. “We’re proud to be New York based journalists who do the hard work that we do,” she said. “But we do it with love, and I think that explains why our audiences continue to grow.”

The Harlem resident, who first came to the neighborhood in 1979 to attend Barnard College, was part of what she calls the “rebel, lefty, community-based, radical New York” at the time. Her career championing for social justice began when she created a radio show on Columbia University’s station, WKCR. It became a forum for listeners to call in and discuss politics surrounding Latinx and people of color in New York City in the 1980s.

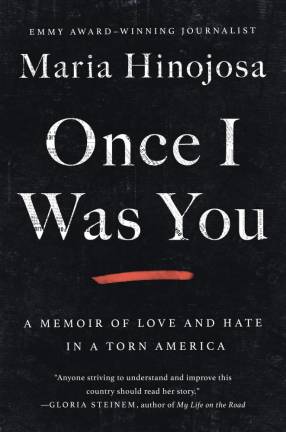

While drafting her new book, “Once I Was You: A Memoir of Love and Hate in a Torn America,” Hinojosa remembered the words of friend and author Sandra Cisneros. She advised, “Don’t always write about the things that you remember, write about the things you wish you could forget.” This led her to uncover her immigration story of coming to America as a baby, when an agent attempted to take her away. Through the persistence of her mother, who refused to let her go, she was able to make it into the country, but reports on the many children who are not that fortunate, which is reflected in the title of her memoir.

Tell us the airport story that serves as the introduction to your book.

I was doing a story back when we were flying around before the pandemic and I end up in McAllen, Texas, on the border. We’re getting ready to take off on a United Flight to Houston and I see this little girl who just looks catatonic. I had now seen children being transported in these ill-fitting sweatsuits, so I was on the lookout for something for this. She was being trafficked. The definition of being trafficked is somebody who does not know where they are going or who is transporting them. Somebody who does not have access to their documents and has been told not to engage with outsiders. I said in Spanish, “I see you because once I was you.”

In your early days in New York, you worked in live radio. I thought it was interesting how you compared that medium then to Twitter now.

I created it because the team at WKCR said, “This is a Latin music night and we are losing our DJ, but we can’t lose those three hours. You’ve got to take it.” And I was like, “Guys, I’ve got 10 LPs.” And they were like, “That’s good enough.” The radio is what we had. We didn’t have cable. [Laughs] Either you were out in the community in the bars, and I really wasn’t much of a bar person myself, or you were listening to the radio. So live radio with commentary was a real thing. People were calling in. They would say things like, “Your Spanish is terrible: why are you on the air speaking Spanish? We love your show, but please, go learn.” And then we practiced. Like on Twitter, you had to be savvy to know who to respond to, who not to and how to keep the conversation going. Tens of thousands of people were tuning in to listen to these conversations, and that’s when I said, “This a part of the New York City dialogue. We are part of it.”

You were one of the first Latinas to be hired in the news division at CBS. What was working the overnight shift like?

It was horrible. I would go to sleep at 7:30 or 8 on a summer night, when it was daylight, so I would have to use face covers and earplugs. I was living in Spanish Harlem at the time. When I was getting up to go to work at 2 o’clock in the morning, people were still partying. Now the flip side to that was walking into CBS News at that hour and the place was popping. Our radio newsroom, which was maybe 20 people, was happening. But it did give me a bird’s-eye view of New York City in the middle of the night, and that’s when I realized that Mexicans had arrived in New York because of one of those 3 a.m. car rides through 116th Street, when I heard Ranchera music.

For a story you did on prisons, you won your first Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award.

I did the story about the murder of Brian Watkins in a subway by a kid named Rockstar. I ended up befriending some of the kids who knew the kids who were involved in this murder and ended up actually writing a book called “Crews.” And one of the guys I met, John, who is a professional right now, we were talking about Rikers Island and I asked him, “Weren’t you terrified?” And he said, “No, I was earning my stripes to go back on the streets and be respected.” And that led me to research it and that’s when I did a story called “Rite of Passage,” looking at how going to prison had become a rite of passage, which it still is, but back then, it was really a different vibe.

The interviews you did with the families of 9/11 will always stay with you. Tell us about some of the people you talked to during that time.

Every day I’d get on the subway and go to Ground Zero or someone’s house in Brooklyn, Long Island or the Bronx who had lost a family member. Certainly, Julia Hernandez will always stay in my heart because this guy from Maine saw the story that I did about her, an undocumented mother who loses her husband at Windows on the World. And this gay man from Maine decides he wants to help and invites her and her whole family to come up and visit and they form a friendship. I think of people who shared with me their last moments of communication with their family. Their last texts. And Rita Lazar, from the Lower East Side, her brother wouldn’t leave his quadriplegic coworker behind, so she lost him.

www.futuromediagroup.org