Pushback on Lenox Hill’s Revised Expansion Plans

Northwell Health’s new proposal meets with opposition from civic associations on the Upper East Side

Northwell Health’s revised expansion proposal for their Lenox Hill hospital has been met with unanimous disapproval by civic associations on the Upper East Side. The plan to renovate and expand Northwell’s Lenox Hill hospital intends to bring the 115-year-old site into the 21st century of health care with an expanded emergency room, state of the art operating rooms and research facilities, loading bays for ambulances and the conversion of all patient rooms to single occupancy rooms. The $2 billion plans for the facility, first reported by Our Town in March 2019, created controversy on the Upper East Side from the start, but the revised plans developed in the spring of 2020 and introduced this fall have failed to reduce local animosity to the project.

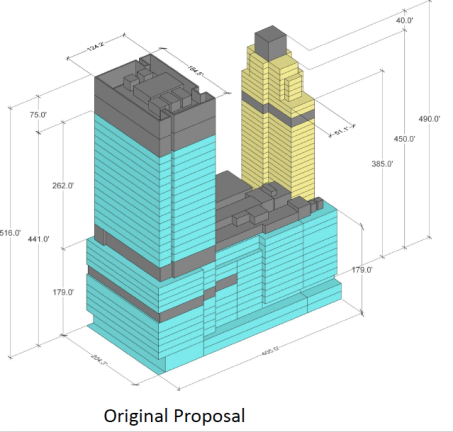

Northwell’s original plans from January 2019 had called for a complete reconstruction of the block that the hospital currently occupies between Lexington and Park Avenues and 77th and 76th streets on the Upper East Side to make way for a 490 foot residential tower on the west side of the campus and a 516 foot tower on the eastern side.

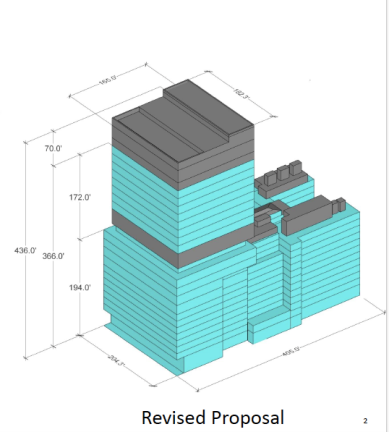

A task force of civic associations, which has met six times since its initial meeting on December 10, 2019, was convened by Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer and City Council Member Keith Powers to create a dialogue between Northwell and the concerned residents of the Upper East Side. The second proposal developed in the spring of 2020 was presented to the task force on October 13, 2020, the first meeting since the COVID-19 pandemic. These new plans eliminated the residential tower, reduced the height of the Lexington tower by 100 feet and reduced the construction timeline by two and a half to three years.

Rachel Levy, executive director of Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts voiced a common concern that the Lenox Hill expansion, combined with a proposal to upzone the midblock New York Blood Center on 67th between First and Second Avenues, will set a precedent for developers looking to rezone parcels in the neighborhood: “These projects will function as a signal to developers as to what is possible in the Upper East Side and undo a careful balance that has been maintained by civic groups and residents.”

Peg Breen, President of the New York Landmarks Conservancy voiced the idea that Northwell was expanding at the expense of the neighborhood: “We’re not a bunch of NIMBY’s, we welcome reasonable growth and for Lenox Hill to modernize, but not at the neighborhood’s expense.” She voiced the sentiment that the task force meetings had been unproductive so far, and had not allowed for Upper East Side residents to make their case to Northwell, a frustration that was also echoed by Levy: “The seven meetings have been carefully orchestrated so that the hospital and its consultants have the floor and get to shape each meeting’s agenda.”

Levy felt that the fact that the hospital’s square footage had actually increased in the second set of plans reflected these inadequacies of the task force meetings, a detail that was obscured in Northwell’s decision to remove the residential tower in the second proposal.

Elective Surgeries

One community complaint is that the state of the art nature of the proposed building would make Lenox Hill a center for high-paying elective surgeries covered by private insurance, rather than a hospital to serve all New Yorkers. In a phone interview, Lois Uttley, the Director of the Women’s Health Program who works with the nonprofit community advocacy organization Community Catalyst, explained that Northwell’s proposal to expand in the Upper East Side, a neighborhood that has been referred to as “bedpan alley,” due to the large presence of hospitals there, would only serve to exacerbate the health care inequality in New York City: “We don’t need more fancy hospitals in the Upper East Side, which has a ratio of 6.4 hospital beds for 1,000 residents.” Uttley said that such expansion and upgrades are needed in outer boroughs like Queens, which bore the brunt of the pandemic, and has a ratio of 1.5 hospital beds per 1,000 residents.

Lenox Hill has maintained the position that the renovations of the hospital are necessary and unavoidable and that the new hospital will be for all New Yorkers, whether or not they are enrolled in private or public insurance. “Elective surgeries can be for colon cancer or breast cancer and we do many nonelective surgeries as well,” Dr. Jill Kalman, the executive director of Lenox Hill explained in a Zoom interview with Joshua Strugatz, the associate executive director and redevelopment projects officer at Lenox Hill. “We serve 72 zip codes of New Yorkers — 56% of our patients identify themselves as nonwhite and 51% are on government paid healthcare systems. It’s unfortunate that the conversation about our expansion continues to be about luxury — our new private rooms are for any and every patient who steps foot in Lenox Hill, regardless of what kind of insurance they have, even if they don’t have insurance at all,” Kalman stated.

But Uttley called Lenox Hill’s track record of serving lower income New Yorker’s “unimpressive,” citing a 2018 report that found that patients using Medicaid only made up 9% of the hospital’s total net patient revenue.

When asked about a frequent complaint amongst members of the task force that no shadow sweep studies or traffic and transportation studies had been shared with its members by Northwell yet, Strugatz said that the studies weren’t completed yet, but once they were completed during the ULURP process with the city, Northwell was excited to share that information with residents. But Rachel Levy stated that once the hospital reached the ULURP process it would be too late for any sort of discussions with residents about the environmental effects that the presence of a 1.3 million square foot, 400 foot tall building on Lexington Avenue, the narrowest avenue on the Upper East Side, might have on the neighborhood.

Ambulatory Centers

George James, an urban planner hired to work with the task force explained in a phone interview that any reductions in the size of the second plan still don’t resolve the issue that the plan is just too big for the site. “They really just need a bigger block. They control the site of the former St. Vincent’s hospital in the Village which is actually underbuilt for its zoning — if they want to expand they could offload some of their programs there.”

Dr. Fred Hyde, a doctor who was hired as well to work with the task force commended Lenox Hill’s desire to transition to single patient rooms, but claimed that the Lenox Hill expansion would provide it with an exorbitant amount of beds for its current patient population: “There’s an increased market nowadays for one day ambulatory surgery — more surgeries are leaving hospitals and going to ambulatory centers, something Lenox Hill could explore at their St. Vincent’s site” located below 42nd street, which is an area that is “a medical desert” unlike the Upper East Side.

Hyde cited statistics that the average occupancy of the hospital is 75% and that average daily attendance of patients has dropped by 30% at Lenox Hill since 2002, which is no fault of the hospital, but is just part of a national trend towards outpatient procedures and Americans visiting urgent care facilities rather than emergency rooms.

Many residents of the Upper East Side remain frustrated with what they say is Lenox Hill’s inability to find reasonable solutions to modernize and expand their hospital without making the community suffer. Patrica Forelle, a member of the task force, felt that ultimately it was unfortunate that the hospital was pursuing such an expansion: “We want a better hospital for them ... it’s too bad they presented these outrageous schemes when we would gladly have accepted reasonable alternatives.”

“These projects will function as a signal to developers as to what is possible in the Upper East Side and undo a careful balance that has been maintained by civic groups and residents.” Rachel Levy, executive director of Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts