a Glimpse Of A DAZZLING, Prolific PAST

BY MARY GREGORY

Few experiences transport us from everyday life, with its traffic, cellphones and crammed sidewalks, more than stepping into the past. And few places offer a better round-trip ticket than the Metropolitan Museum.

“Court & Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs” offers a glimpse of life in the years 1037 to 1308. The Seljuqs, a Turkic dynasty of Central Asia, were nomadic, prolific and progressive. They conquered lands across Turkmenistan, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey, and spread traces of their artistic, scientific and literary advances as far as Alexandria in Egypt.

The exhibition starts with maps and historical information flanked by a pair of almost life-sized painted warriors that once guarded palace doors but now welcome visitors. They lead the way to a dazzling array of objects that attest to the wealth and power of Seljuq rulers, but also their inquisitiveness, invention, openness and acceptance. Under Seljuq rule, astonishing scientific and medical advancements were made, poetry and literature flourished, metallurgy evolved, and perhaps most remarkably given the world we live in, great religions coexisted peacefully.

The exhibition is presented in six sections: Sultans of the East and West; The Courtly Cycle; Science, Medicine, and Technology; Astrology, Magic, and the World of Beasts; Religion and the Literary Life; and The Funerary Arts. The first and second galleries focus on the rulers and their courts, an early version of lifestyles of the rich and famous. Gold medallions, coins, plaques and just about anything, including an inscrutable Sultan Tughril, that could be inscribed with a sultan’s name is included here. The Courtly Cycle includes the magnificent Blacas Ewer, a masterpiece of metalwork created in 1232 in the city of Mosul. Yes, the same Mosul we hear about on the nightly news once housed the greatest metal smith shops in the world. The Blacas Ewer weaves copper and silver into charming vignettes depicting musicians and dancers, hunting scenes, eating and merriment.

For leisure time, there’s a backgammon board and a cup inscribed with a poem extolling the virtues of wine. An elegant dish in turquoise shows an ud player with inscriptions on the side wishing “lasting happiness” and advising “make short all long speech” — still good advice at a party.

The sections focusing on science, medicine, technology and magic amaze. The Seljuqs built hospitals and medical schools and performed surgery and dentistry. Manuscripts describe medical preparations. They’re presented alongside pincers and probes and a fearsome surgical saw from the 11th-12th century that now sports green patina. To be on the safe side, protective inscriptions decorate the blade. A silver apothecary box looks much like today’s version of a seven-day pill container. A gold dental hook looks drastic, but augurs a less severe outcome than death by infection.

From the realm of astronomy, there’s a clever astrolabe with interchangeable dials, and a stunning celestial globe made in Iran in 1144, delicately carved with constellations and planets. An ingenious lockbox used spinning dials with letters that had to be lined up before the lock yielded. Evoking a distant interior world are treatises on spells and magic that seem to contradict the Seljuq’s scientific inquiry, though, at the time, they were considered as valid as medicine or astronomy.

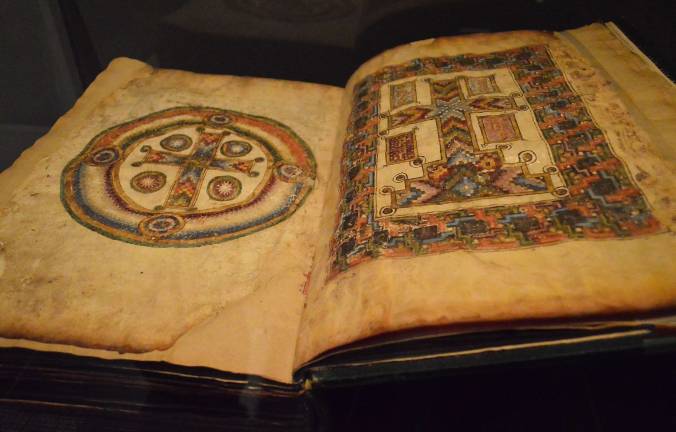

Heading into the sections covering religion, magnificently carved walnut mosque doors lead to a room filled with stunning, lavishly decorated Qur’ans displaying the height of calligraphic artistry. Alongside them are Orthodox Christian texts with similar design elements penned by monks in Syria and a cup with Hebrew inscriptions in Seljuq metalwork style.

Last year, when the treasures at the Mosul Museum were threatened and later destroyed, Thomas Campbell, the museum’s director, and The Met issued the following statement: “This mindless attack on great art, on history, and on human understanding constitutes a tragic assault not only on the Mosul Museum, but on our universal commitment to use art to unite people and promote human understanding.” The Met was rare and early in its wake-up call. This year, the museum has gone further in reminding visitors what marvels have been produced and may be forever lost in this important part of our shared world.

The astonishing ingenuity, touchingly human playfulness, elegance and beauty expressed in art, poetry, spirituality, science and technology, in the works in “Court and Cosmos” when seen in context of the political realities of the 21st century bring to mind the words of Omar Khayyam, the great poet born under Seljuq rule. “Your hand can seize today, but not tomorrow; and thoughts of your tomorrow are nothing but desire. Don’t waste this breath.” We all share the history of mankind. Don’t waste this chance to see this moving reminder.