A Jewish Treasure from the Middle Ages

A new exhibit offers a rare glimpse of a single family’s life, and its dark fate, more than 600 years ago

By Mary Gregory

When Dr. Barbara Drake Boehm, senior curator of medieval art at The Met and The Cloisters, was approached by the Musée de Cluny about works that might be available for loan while the Parisian medieval museum undergoes renovation, she knew right away what she'd ask for.

"The Colmar Treasure," the exhibition she organized, is on view at The Cloisters through January 12th. It's comprised of rare, important, and beautiful works from the middle ages. There are gems, gold and silver, but not mountains of them. What imparts treasure status to this cache is the story it tells, and while it may not be unique, once known, it's unforgettable.

"When they hear the word treasure in a title," says Boehm, "people think of a pirate's hidden treasure – 'X marks the spot' and you dig in the sand, and there's a big chest and coins are spilling out of it. This is 300 silver coins; some of them are really small. What makes this a treasure is not its cumulative weight in silver and gold. What makes this a treasure, I think, is it allows us to see both the good and the bad of medieval society at that time." While much of the art that survives from the middle ages comes down through churches and monasteries, Boehm says she always strives to broaden perspectives, and "that brings me to medieval Jewish artistic heritage, so it was an obvious choice for me."

Wedding Rings, Gifts and Heirlooms

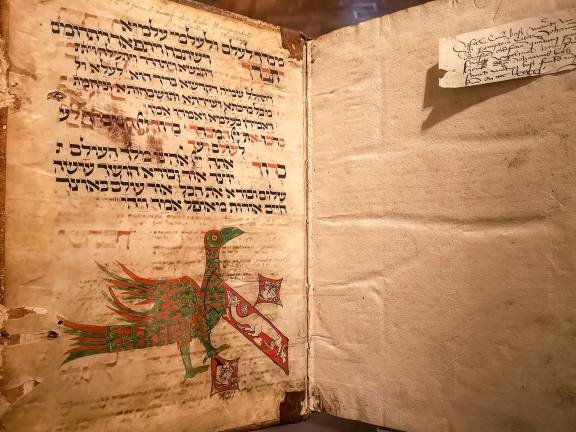

Buried in a wall in a confectioner's shop in a picturesque town in the Alsace region of France, and uncovered by workmen in 1863, this bundle of valuables was hidden by members of the Jewish community in the early 1300s. There were rings, coins, a silver studded belt and headband, buckles, silver cups, an extravagant brooch, and one rare and spectacular wedding ring. Shaped like a roofed building, meant to recall the Temple in Jerusalem, and inscribed with the Hebrew words, "Mazel Tov," or good luck, it's part of what identified the owners as Jewish.

When the trove was spread out and photographed by the Musée de Cluny at the time of acquisition, it looked like the kinds of things you might have in your own safe deposit box today. And that's what gives these works their emotional punch. They're relatable. This isn't some glittering pile of diamonds worn by nobles and royals, but the savings and significant items – wedding rings, gifts and heirlooms – of a single merchant or working-class family. They were treasures to them. The objects date to several decades, indicating possibly more than one generation. Why were they hidden? What stories does the exhibition reveal?

A Plague and a Pogrom

In the early 14th century, Colmar was a thriving small city on the Rhine, in the heart of wine country. Boehm found records of a small Jewish community that lived peacefully alongside the larger Christian population, through documents showing amicable business relations. The community was small – fewer than 100 individuals, possibly half that many – but confident enough in their future in the town to have built a synagogue, a school, and a mikveh, or ritual bath. Then, in 1348-49, Boehm explains in the texts and accompanying book, a pandemic of bubonic plague swept the region. Scapegoats were sought and, sadly, found. People accused Jews of poisoning the wells, and Colmar burned its Jewish citizens to death.

It wasn't the only or even the most devastating pogrom to befall Europe's Jewish community, but the intimacy and familiarity of the objects that belonged to this one family and the testament they give makes "The Colmar Treasure" particularly poignant and touching.

Though the objects have been studied and kept in a museum for almost a hundred years, Boehm is the first to be able to attribute them as belonging to a single family. "For me it's much easier to look at a treasure that size and say oh my gosh, that was a family. That family lost their lives." She even discovered an inscription "ANCH" which translates to a diminutive for the name Anne. "I like to think that a certain Annie was a member of the family," she says. Perhaps it was she who wore some of the rings we see, or the headband, more than 600 years ago.

Boehm ends the show powerfully, with a woodcut from a book published about 200 years after the massacre. In it, the renowned cartographer and Hebrew scholar, Sebastian Münster, recorded 8 churches, but no hint of a synagogue, school, or any other reminders of the Jewish community. It had simply vanished.

A Bridge Between Worlds

"The Colmar Treasure" is the kind of exhibition that touches, and then lingers. What does Boehm hope visitors will find? Along with the beauty of the works, "I want them to experience these objects on a very personal level as if they were handling something that belonged to their own mother. I want that kind of visceral response to the sense that somehow these things carry something of the person who owned them," she says. "What I hope they take away from it is actually something of that same feeling. That the world that these people lived in is not so different; their daily experience is not so different from our daily lives. And sadly some of the tragedies from the past are not so distant from some of the tragedies of our present. I don't mean to collapse history," she adds, "but I do mean to bridge our worlds."