da Vinci, Now in knots Exhibition

Any time there’s a work by Leonardo da Vinci on view anywhere in the Northeastern U.S., it’s worth considering a trip. Any time there’s one in New York, it’s practically a no-brainer. The Metropolitan’s exhibition Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620 opens with a fascinating look at a group of woodcuts showing complex, elegant knot work designs thought to be embroidery patterns. The woodcuts were made in da Vinci’s workshop after his original designs.

Da Vinci was drawn to knotty problems, and to knots themselves. In his intellectual and artistic circle, knots both signified complexity and symbolized infinity. Here, he formed them into a graceful circular motif of geometric perfection. His original six patterns were so stunning and so significant that an artist no less than Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) decided to copy them.

Associate curator Femke Speelberg, who organized the exhibition, explains in a blog post that Dürer “encountered the prints during a trip to Italy undertaken between 1505 and 1507. Copying after other artists was uncharacteristic for the famous artist from Nuremberg, but the ingenuity and appeal of these designs led him to set aside his scruples and create the woodcuts, to be able to share the beautiful designs with his northern colleagues.” She also noted that Dürer’s conscience didn’t allow him to place his signature on another artist’s design, but that didn’t bother the subsequent owner of the woodblock, who didn’t hesitate to carve an AD insignia in the center of the design to spur sales. The very rare woodblock itself, along with the original da Vinci that inspired it and Dürer’s homages are all on display.

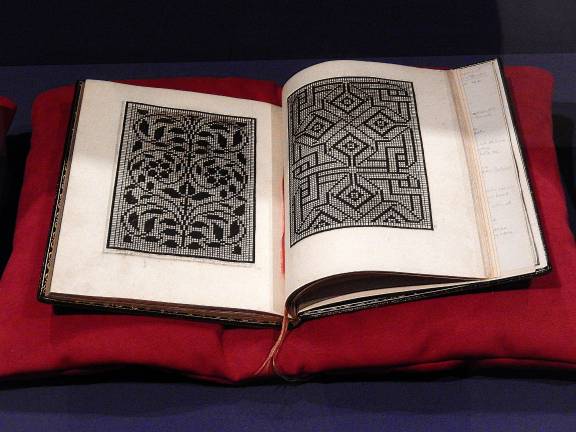

The exhibition, filling the first floor of the Lehman wing through January 10, goes on to explore the creation, dissemination and popularity of printed pattern books made between 1520 and 1620. They were the original fashion magazines, and they became wildly popular in Renaissance Europe. One look at the paintings of the period in the galleries upstairs will show that these people took their clothes seriously. Lace collars and jeweled hems sewn together with golden threads adorn both secular leaders and saints.

The Met has one of the world’s finest collections of these pattern books, and seeing them on display is extremely visually engaging. But seeing them grouped among samples of the final product, either as textiles or garments, or in paintings of sitters wearing them, brings it to a whole different level. And tracing how these early patterns influenced subsequent designers and craftspeople for centuries underscores the tremendous historical significance these early patterns had.

The exhibition includes a touching and gentle painting by Francisco de Zurbarán of the Virgin Mary as a young girl, caught in a moment of spiritual communion as she is embroidering. The wall text makes the point that needlework was thought of as a virtuous occupation for women, as opposed to racier pursuits like singing, dancing or playing cards. Depictions of Mary at needlework were common throughout the Renaissance, and young women’s education included sewing lessons well into the 20th century.

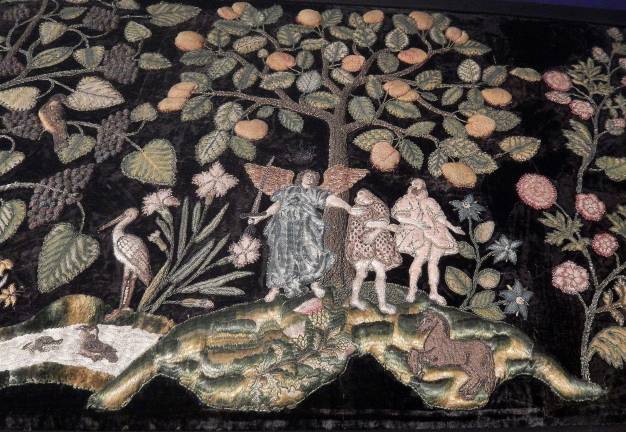

While the show incorporates several examples of humble, homespun textiles, like the charming sampler done in 1669 signed by “I.S.” an unknown girl of just 10 years of age, the spectacular works are jaw-dropping showstoppers. There’s a silk velvet panel embroidered with a depiction of the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden done in England in the late 16th century. It stretches over six feet and shows, under a spreading apple tree, Adam and Eve on the left, covered by leafy embroidery. Below them is a river populated with swimming fish and floating ducks and a bank of blossoming flowers all depicted in thread. In the center is God, robed in rich red and crowned with an embroidered gold halo, angels flying above him. And at the right, the angel escorts them from Eden. It’s nothing short of virtuosic.

One room features a whole wall of patterns realized—drawings and textiles placed side-by-side. Also on display are works from Mexico to Bhutan, from the 1500s to the present, and ecumenical and everyday garments that remind us that we all gather under one great robe, or, more prosaically, that we all put on our pants one leg at a time.

An opportunity to see so many works from so many different departments—prints and drawings, the Costume Institute, European Paintings, as well as international loans—coming together to form a new way of understanding the evolution of fashion is rare and delightful. A chance to see a da Vinci of any kind is not to be missed. And for anyone who’s ever tried his or her hand at turning a paper pattern from Simplicity into a wearable garment, this show will boggle the mind.