faith and photography

Auguste Salzmann, a French photographer whose work is strong enough to get into the Metropolitan Museum of Art, has never had a one-man show before. He died in 1872. “Faith and Photography: Auguste Salzmann in the Holy Land” presents a collection of his evocative and beautiful black and white images of landscapes and architecture in and around Jerusalem. The exhibition, curated by Anjuli J. Lebowitz and Jeff L. Rosenheim runs through Feb. 5. Comfortably filling three rooms with rare salted paper prints, it’s aesthetically and historically captivating and rewarding.

Salzmann was born to wealthy parents and studied art, but his interests and abilities exceeded narrow definitions. He chose not to enter the family textile business, but rather to pursue a career as a painter, exhibiting in the salons of Paris. Possessed of a restless mind and seemingly boundless curiosity, as his interests grew, so did the realm of his studies and his capabilities. Salzmann’s Christian beliefs and fascination with the past led him to study biblical archeology, and he was among the earliest artists to dabble with the camera. He had the particular set of skills needed just when the right opportunity arose.

In 1850, Louis Félicien Caignart de Saulcy, the French archeologist who would later conduct the first dig in the Holy Land, returned from an expedition with drawings that he claimed proved that many of Jerusalem’s buildings and sites dated, at least in part, to the time of King Solomon. Critics ridiculed him, finding the idea laughable, and fellow scholars suggested that he falsified his hand-made documentation.

Salzmann joined the fray in 1853, lugging his equipment to a city few archeologists visited during the era of Ottoman rule. He wasn’t attempting to create travel photographs, and he didn’t. Rather, he focused tightly on the religious structures — the temples, churches and mosques — that fill Jerusalem. By letting his camera record specific sites and isolated architectural details, he let the facts, as presented in stark black and white defined by the blinding desert sun, speak for themselves. They confirmed de Saulcy’s drawings. On Salzmann’s return to Paris, de Saulcy described his satisfaction at having been vindicated by no less a witness than the sun.

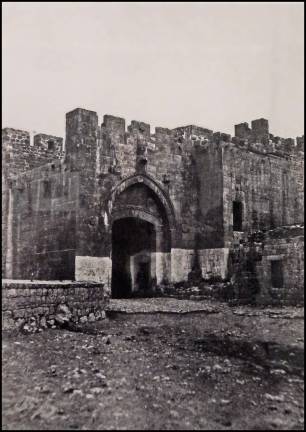

It took him four months for Salzmann to record what would become an album of 174 prints; the exhibition presents about 40. The images give an impression of a city ever in the past while also ever in the present. Visitors today look up at the arches and gates, domes and walls depicted in the photographs. But the experience of seeing them in these prints feels strangely personal and immediate, since Salzmann’s images are completely devoid of people. There are no cars or fashions to date or muddle the picture.

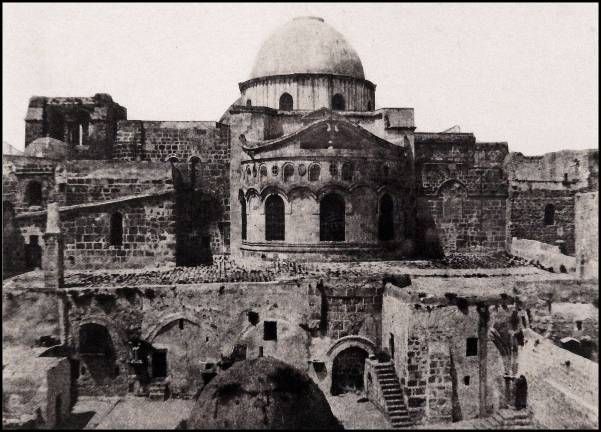

We see only buildings, foregrounds and clean white sky. Whether sweeping vistas, as in the view of the Dome of the Rock from outside the city walls, or in complex patterns of brickwork or carved stone that decorate the structures, the crisp tones and minimalist aesthetic appeal to modern sensibilities. Yet, we never step into the realm of the purely visual. These are, after all, images of some of the most revered religious sites in the world. A photograph of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with its domes, stairways, windows and multiple facades, the outcome of centuries’ worth of building and rebuilding, is a trove of details that document not just history, but the many faiths that hold this particular place sacred.

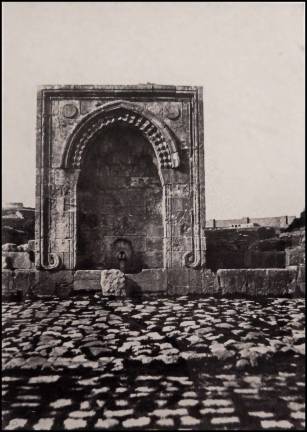

“Jérusalem, Fontaine Arabe, 2” shows one of six fountains built by Süleyman the Magnificent in 1536–37. The composition uses positive and negative space, squares and arches, and endless gradations of gray against an empty background to enhance the monumentality of the structure.

In another work, “Jérusalem, Tombeau des Juges, Détails,” just inside the entrance to the tomb are barely visible traces of 63 individual rock-cut tombs within.

The rich blackness of the opening, utter in its darkness, expresses more than just the formal qualities of the architecture. It’s a gaping mouth, echoing eternity, into which few visitors would likely venture. Salzmann was, after all, a scholar with an attentive scientist’s eye, a believer’s faith and an artist’s romantic soul.

Salzmann’s photographs both capture the beauty of the city and evoke a sense of wonder. In “Faith and Photography” we see evidence of the march of millennia, but feel Jerusalem as a place where time seems to somehow stand still.