Fall Under the Power of Prints at the Met

The Metropolitan started collecting works on paper 100 years ago. To commemorate the anniversary, the museum has put together a collection of their highlights, “The Power of Prints: The Legacy of William M. Ivins and A. Hyatt Mayor.” Boasting hundreds of thousands of works, from medieval manuscripts to subway posters, no other collection has the depth, breadth and unique flavor as the one begun by two early, avid and idiosyncratic curators who are paid homage in the exhibition.

Three large galleries are filled with the profoundly beautiful, the oddly curious, and the occasionally funny. William Mills Ivins, the founding curator of the department of prints, and Alpheus Hyatt Mayor, his successor, collected certain works for their importance, others for their beauty, some for their historical relevance, and many for the sense of American culture they were able to convey. The show, organized by associate curator Freyda Spira, covers works from the Medieval and Renaissance through Impressionism, up to the mid-20th century, with pieces as diverse as religious scenes and baseball cards.

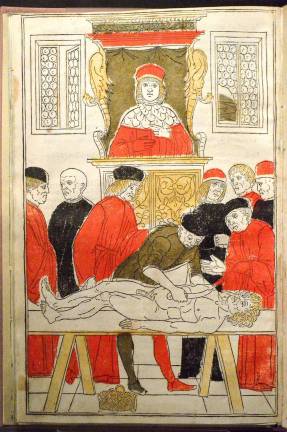

Some of the earliest pieces fill an extraordinary bookshelf. Manuscripts from the 1400s and 1500s open onto pages adorned with images from early texts on medicine, botany, mathematics, astronomy, travel and artistic techniques. A book on military strategy suggests disguising your battering ram as a dragon to terrify your enemy. A medical volume from 1493 even offers a how-to picture. It’s more than a display of books; it’s a glimpse into the history of human knowledge and ingenuity.

Throughout, this is a show made up of show-stoppers. Three versions of Rembrandt’s 1653 powerful crucifixion scene hang side-by-side, allowing us to follow the changes he made in details, highlights and shadows and see how his vision and the work evolved. Take a look at “The Death of the Virgin” to witness Rembrandt’s ability to employ composition to express deep meaning. The picture is roughly built of two triangles — a dark one on the bottom, filled with people, pointing upwards, and a light filled triangle above, pointing downwards, populated by heavenly beings. The plane on which they meet is where Mary, who belongs fully to neither world and to both, lies.

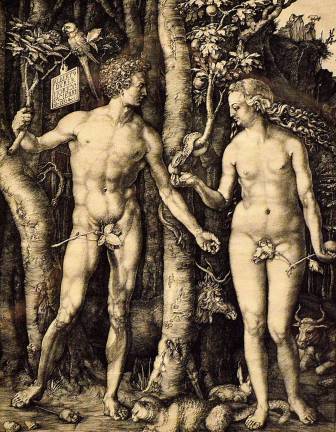

It’s not hard to find images of Albrecht Durer’s “Adam and Eve” (1504) on the web. It’s not easy to find a chance to stand in front of it. Full sized, placed at eye-level, it draws the eye into a paradise of imagery. There are delightful creatures — a mouse and cat, a snaily looking snake with four antennae, a lushly plumed parrot — and the most gorgeous apples imaginable.

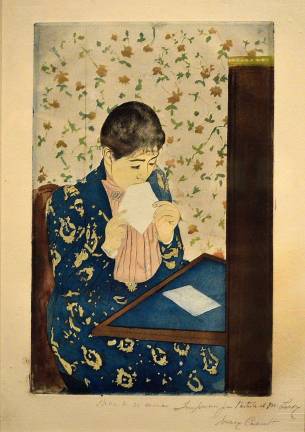

Mary Cassatt’s “The Letter” looks lovely despite how radical it was when she made it. Next to it, a piece by her good friend, Edgar Degas, shows Cassatt as the subject. In a nighttime scene in Venice, with just a few scratches of line and washes of shadow, James McNeill Whistler builds a sense of fog and damp so palpable you might look down to see if your feet are wet. An Edward Hopper street scene and a lone figure in an empty bedroom hint of 20th century realities, through that artist’s eyes.

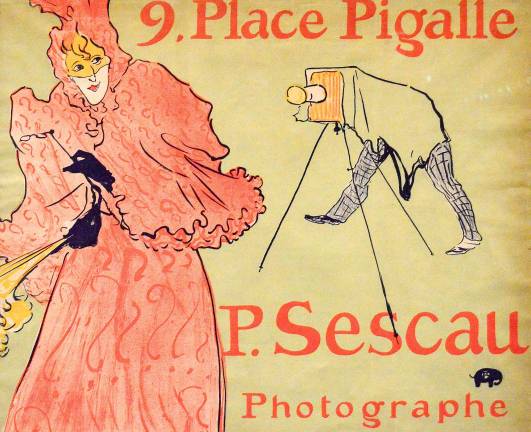

The third gallery bursts into color, as though we’ve landed with Dorothy in Oz. Toulouse-Lautrec’s bold pinks and Moulin Rouge advertisements bring us to Belle Époque Paris, while in the States, a posters craze was raging. Magazine and chapbook covers and calendars designed with eye-catching graphics and intense colors passed modernist visions to the masses.

One of the points the exhibition tries to bring across is that even these early printed works influenced our current information age. Precursors of the never-ending stream of images coming at us from unexpected sources can be found in two delightful cases filled with carefully preserved objects that were never meant to last. Many were given away to reward or tempt customers.

Trading cards, paper toys and memorabilia from events like the 1934 World’s Fair are bright, fun and appealing even today. Pitchers and catchers poised against glowing orange Maxfield Parrish-style skies give baseball a gorgeous allure. What kid wouldn’t have loved finding beautiful pictures of Snow White tucked into a loaf of Donald Duck bread or lithographs of snazzy cars hidden in a cookie box? There’s even a series of cards of movies stars distributed by the Koester Baking Company. Could a young Andy Warhol have been collecting them? It’s interesting to imagine. Seeing 550 years of collective thought expressed in glorious line and brilliant colors reminds us that art is indeed long. But the exhibition, and the chance to see this many masterpieces that, due to their fragility, spend much of their lives out of sight, only runs through May 22nd. Catch it.