It Was His Kind of Town

BY VAL CASTRONOVO

Max Beckmann (1884-1950), the famous German Expressionist artist, loved New York. He arrived in September 1949, by way of St. Louis, where he taught for two years at Washington University. Beckmann dubbed the city “a prewar Berlin, multiplied a hundredfold.” He was enthralled by the buzz, “fantastic ... utterly fantastic ... Babylon was a kindergarten by comparison, and here the Tower of Babylon is transformed into the mass erection of a gigantic (and perhaps senseless) will. My kind of thing.”

So it seems ironic that Beckmann almost never painted cityscapes in the 16 months he lived here. He walked the streets endlessly, but he painted interior landscapes, especially bars, restaurants and hotel lobbies. He craved the nightlife and was a patron of vaudeville and cabarets. Per curator Sabine Rewald in the catalog, he frequented “places where he could observe the spectacle of life passing by. He regarded the world as Welttheater (world theater).” However, his favorite subject, we learn from this thrilling new show, was himself.

“Max Beckmann in New York,” an exhibit of 39 works produced in the city or now in New York collections, opens with seven colorful self-portraits created between 1923 and 1950, the year Beckmann died. The organizers remind us this modern artist, so revered today, was proclaimed a “degenerate” by the Nazis in 1937 and had his works confiscated from German museums.

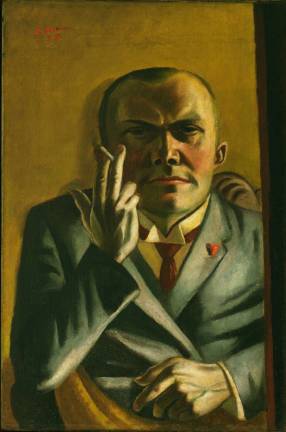

In the first gallery, the cosmopolitan painter appears confident and well dressed. He favored jacket and tie — tuxedos, too — and cigarettes. An early image, “Self-Portrait on Yellow Ground with a Cigarette” (1923), shows Beckmann suited up, with high collar and matching red tie and lapel pin. “[H]e might be mistaken for a successful businessman,” Rewald writes, noting that he typically omitted the symbols of his trade, painter’s brush and palette, in the 80 selfies he executed in his lifetime. One artsy flourish: the yellow shawl draped across his lap, matching the picture’s yellow background and lighting.

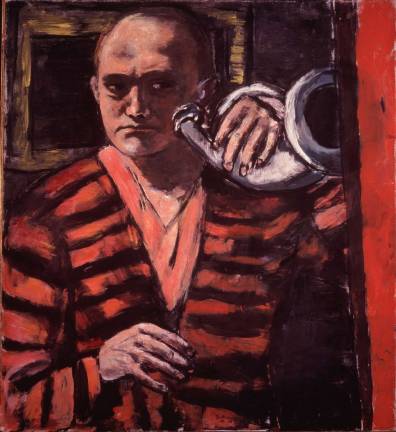

The other self-portraits employ interesting props, especially headgear — a sailor’s hat, a derby, a visor and, in the year after he was vilified by the Nazis, no hat but a bugle. “Self-Portrait with Horn” (1938) was described by one writer as, “one of the most earnest, most philosophical of his paintings.” The colors, black, red and yellow, echo the colors of the German flag before the Nazis changed it in 1933. A blackened mirror frames Beckmann’s head.

In 1925, he married Mathilde von Kaulbach (“Quappi”), the daughter of a prominent artist. A violinist and singer, she was 20 years younger than Beckmann and the subject of some of the most beautiful portraits here. The couple sought voluntary exile in Amsterdam after the Nazis denounced Beckmann and remained there for the duration of the war. Many dining and drinking establishments were shuttered during the occupation, so the painter had to imagine them in his art.

The third gallery is a showcase for the Amsterdam years and Quappi’s style and sophistication. “Quappi with White Fur” (1937) depicts the artist’s wife in a veiled hat standing in what appears to be a luxe hotel foyer. The adjacent canvas, “The Oyster Eaters” (1943), pictures her diving into an oyster in a fish restaurant, flanked by her daughter-in-law, Tutti. Both of the women are fashionably decked out — Quappi, once again, sports a hat with a veil, Tutti wears one with a feather. As the curator writes, “Beckmann took great pleasure in the good things in life.” He relished fine food, drink, clothing and all things posh.

The post-exile years in St. Louis and New York follow, introduced by the elegant “Quappi in Gray” (1948), the last portrait the artist painted of his wife, who was 44. She wears a chic gray coat and toque and looks perfectly serene. The bohemian artist’s enchantment with haute hotels is wonderfully expressed in the side-by-side scenes of the Palm Court at the Plaza (“Plaza [Hotel Lobby],” 1950) and the King Cole Bar at the St. Regis (“Café Interior with Mirror-Play,” 1949, though it’s an image of the bar’s interior). Beckmann regularly headed to the Plaza after work for “recovery cocktails” and people watching.

Other rooms feature his wildly inventive allegorical works and two of his nine triptychs, including the famous “Departure” (1932, 1933-35).

New Yorkers will appreciate the city notation. The Beckmanns moved to Manhattan in the fall of 1949 after the painter was offered a teaching post at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. They lived on the third floor of a townhouse at 234 East 19th St., before relocating to a first-floor apartment uptown, at 38 West 69th St.

On Dec. 27, 1950, Beckmann left the apartment to see an exhibit at The Met featuring his recently completed “Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket” (1950). He never made it to the museum. He was stricken with a heart attack on Central Park West and 69th Street, a sad fact that gave impetus to the current retrospective — 66 years after he died on a street corner at age 66.