Klimt’s Muses and Mosaics Sparkle

BY MARY GREGORY

Somewhere between the 19th century and the 20th, between Impressionism and Modernism, between realism and abstraction dwelt Gustav Klimt. He utilized tools from both fine art and decorative, techniques from several early Modern schools and the thinking of the Symbolists to create a body of work that’s unique at the same time it references so many others’. His work reflects the changing ideas and realities of one of the most dynamic inflection points in human history, by bridging, borrowing and blending what he found.

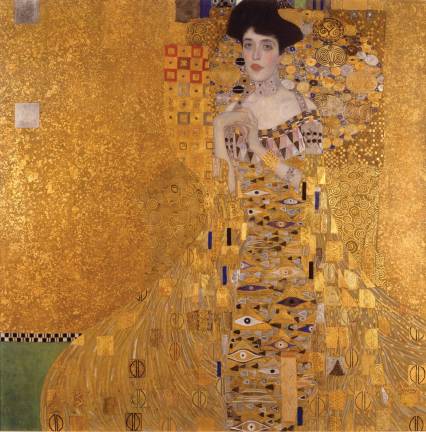

We tend to call to mind a favorite Klimt when we think of his work, often the famous “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I,” also known as the “Woman in Gold” from the movie about it. But seeing several of his major portraits at the same time affords richer understanding of his work, his genesis and evolution, and his place in the pantheon of most expensive artists of all time (the “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I” shattered previous worldwide art sales prices, going for a record $135 million in 2006).

Through Jan. 16, the Neue Galerie celebrates its 15th anniversary with a special exhibition bringing 12 portraits and some 40 drawings together in “Klimt and the Women of Vienna’s Golden Age, 1900–1918.” They fill the museum’s second floor and are complemented with furnishings, jewelry and fashions that give a sense of that particular moment and place.

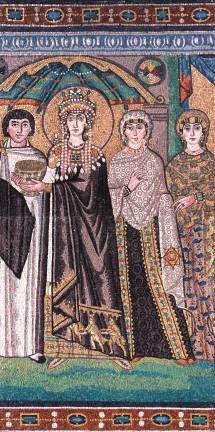

But to have a better understanding of these works, you have to go back to the sixth century, or at least Klimt did. In 1903, the artist made a trip to Ravenna, Italy, and visited the Basilica di San Vitale. It’s one of the most important surviving examples of Christian Byzantine architecture in Europe and it houses dazzling mosaics done between the years 525-547. Their abstracted, flattened portrayals, rich decorative patterns and backgrounds, and their glimmering gold and silver surfaces caught the light and captured at least one artist’s imagination. They also spoke to modern artistic visions that were stepping away from perfection in representation.

Klimt was deeply affected by them. He wrote home to friends and colleagues about them. The full-sized portrait of the Empress Theodora so influenced his vision that he embarked upon on what’s referred to as his “Golden Phase.” The apogee of this period is the pride of the Neue Galerie’s permanent collection, the 1907 portrait, “Adele Bloch-Bauer I.” The curators wanted so much to highlight the importance of the Ravenna mosaic of Theodora to Klimt’s depiction of Adele Bloch-Bauer that they included a recreated version done by craftsmen from Ravenna as part of the exhibition. In the foyer outside the gallery you can tilt your head back to view the towering figure of Theodora, flattened, gazing directly down towards the viewer, surrounded by countless shimmering golden bits of glass and imagine how it would have affected Klimt. Then you can step into the gallery and see. It’s an extraordinary experience.

Small squares of silver and gold leaf glisten in the painting, as they do in the mosaic, yet Klimt has varied their sizes, shapes and tones. As in Theodora’s mosaic portrait Klimt’s figure is fully covered by a flowing gown that really gives no hint at a body with arms or legs or contours of any sort beneath. It’s only Adele Bloch-Bauer’s head, rising above a thick band of jewels, just as Theodora’s does, and her hands (also just as in the Theodora mosaic) that give an idea of the woman portrayed. And what an idea it is. These are two women that seem as strong and lofty as they are drop-dead gorgeous.

All of Klimt’s subjects — of which almost all are women — are portrayed in the most flattering terms. They’re soft, sometimes delicate, individualized and recognizable women and girls that lived in a moment in which women were reaching beyond the traditional boundaries of family and child-rearing. Strong, confident personalities look back at the viewer, despite the gauzy dresses and flushed cheeks their wealthy husband patrons expected. These were the women of the days of Suffragettes, Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf and Isadora Duncan. Klimt’s subjects were among the leaders of an elegant, advanced society.

Klimt’s oeuvre is filled with beauties, and while each has her own story, together they tell the artist’s. An early work, “Girl in the Foliage” almost resembles a Sargent society portrait. His “Portrait of Gertha Loew” in soft a white gown against gray recalls Whistler’s “arrangements” and early steps into abstraction. “The Black Feathered Hat” could be by Egon Schiele. “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II” and “Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer” display Klimt’s interest in Asian art, and his colors speak to Fauvism. One gallery presents historic photos along with many preparatory sketches for the so-called “Woman in Gold.” In them, Klimt focused on the posture and costume, but left the face blank except for prominent lips, which reveals more about the artist than the subject.

To see this many major works by Gustav Klimt together is extremely rare, due to the enormous value of each work. But to see them just inside galleries presided over by the Empress Theodora, perhaps the woman who most profoundly touched Gustav Klimt, is exceptional.