soup and sides — Andy warhol at Moma

BY MARY GREGORY

Any major Andy Warhol exhibition is sure to attract enthusiastic audiences. He’s one of the best known artists of his epoch. He created images that even schoolkids recognize at a glance, and he was among the artists that developed Pop Art — one of the most significant movements in 20th century art. The Museum of Modern Art has gathered dozens of Warhol’s iconic works together for a quiet, scholarly and fascinating exhibition.

Wait. Did we say quiet and scholarly and Andy Warhol? Indeed we did.

“Andy Warhol: Campbell’s Soup Cans and Other Works, 1953–1967,” which runs through October 18 in the second-floor Prints and Illustrated Books Galleries, fills three rooms and brings together an intriguing group of early works, all 32 of Warhol’s famous Campbell’s soup can paintings, and a several major silk screens from the 1960s. There’s something for everyone, from pensive pencil drawings to multiple big, splashy Marilyns. Together they paint a picture of an artist you know, but from a perspective you might not.

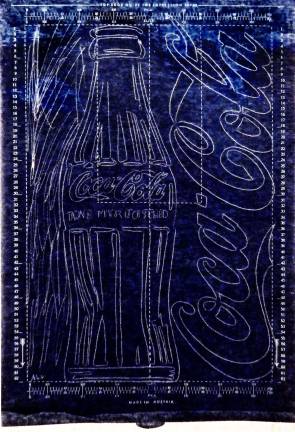

The first gallery presents early works — watercolors, drawings, gouache paintings and even a group of mimeograph works. Do you remember mimeographs? If so, don’t admit it. It’ll date you. Warhol knew about them and, like a true artist would, he used them in a way no one else seemed to have ever imagined. MoMA’s collection includes four compositions done in 1962, in response to a request for works that could be reproduced and sold inexpensively through the Pasadena Art Museum. One of his early shots at multiples, they’re etched into the dark blue background of the pre-inked paper. This group, including a shapely Coke bottle and a soup can, was, the curators point out, never used to run off copies, so the lines are pristine.

The subject is worlds away, but the technique and the clarity and economy of line recall etchings by earlier artists, from Matisse all the way back to Rembrandt.

Filling the opposite wall is a charming group of watercolor paintings of shoes. Warhol started his career as a commercial artist. In the 1950s and ‘60s some of the biggest stores and magazines sported Warhol creations, in the forms of ads, layouts and window displays. There was a stint from ‘55 to ‘57 when he was the official illustrator for the I. Miller shoe company.

Warhol painted a new shoe each week for ads that ran in The New York Times. The series is wittily, if somewhat irreverently, titled “À la recherche du shoe perdu.” They’re bright, bold and utterly charming. Each has a clever little line of text in Warhol’s mother’s uniquely squiggly script (or that of assistants who imitated her penmanship) that feels like the start of a limerick.

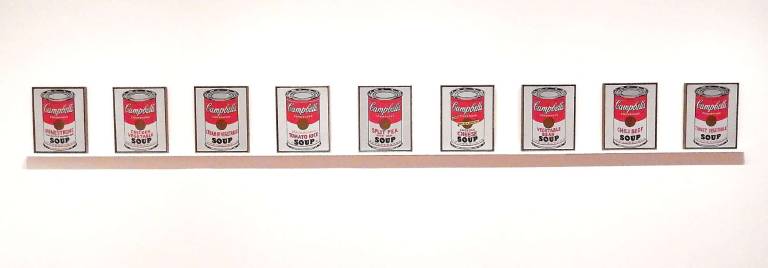

Interestingly, the middle gallery, in which the soup can paintings are displayed, was less crowded during the times I visited. It’s hard to think of more iconic works of art. They’re presented on shelves about chest high, without their traditional Plexiglas frames, giving a chance to get up close and personal with the entire series. Organizers Starr Figura, a curator in the museum’s Department of Drawings and Prints, and Hillary Reder, a curatorial assistant in the department, have made every effort to engage the viewers, offering history and background for the works, even pointing out that the gold fleur-de-lis shapes that decorate the cans were made by a rubber stamp Warhol fashioned from an eraser. Certainly this group of works made a major impact on the trajectory of art of the 20th century. Warhol, with these small, simple paintings, the curators state, “subverted the prevailing notion of art as individual, expressive, and original.” And that’s absolutely true.

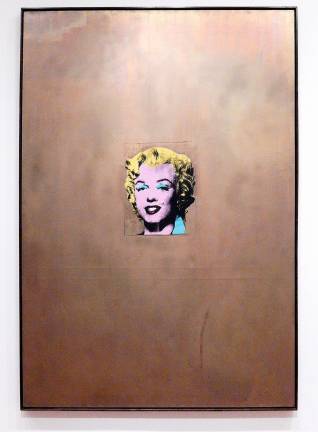

He was also among the first artists to react to a tidal wave of imagery sweeping through America’s consciousness via name-brand advertising, which grew ubiquitous as televisions moved into homes en masse. From this standpoint, the small paintings are monumental. From the standpoint of standalone paintings, they are, as he intended, repetitive. Don’t blame yourself if, after seeing Turkey Noodle, Tomato, Onion and Clam Chowder, you wander, as many visitors did, into the next room where a dazzling group of Marilyns, a towering Elvis and dark and poignant Jackies await.

But, the draw may also be because the wall of multi-colored Marilyns and Warhol’s own self-portrait apparently make the perfect backdrop for selfies. Lots of visitors were availing themselves to of the chance to be pictured with not one, but two celebrities — Warhol and Monroe. It’s a moment for both art and fun, and that’s fine.

MoMA, like many other museums, has been making great efforts to engage audiences beyond its doors. Images of all of the works and loads of information are available online. Still, nothing beats going to see these creations in person and drawing your own conclusions about how and where they fit into your understanding and vision of art.

Andy Warhol was both prescient and provocative. He challenged and changed. He could be funny. Heaven knows, he could be scandalous. But, as the works in this show remind us in many ways, he was also a great artist.