A Church's Milestone Anniversary

The Unitarian Church of All Souls celebrates its 200th year. An excerpt from its official history tells the story of its role in the Civil War.

The Unitarian Church of All Souls last month celebrated its 200th anniversary as a house of worship that embraces everyone, regardless of their religious views.

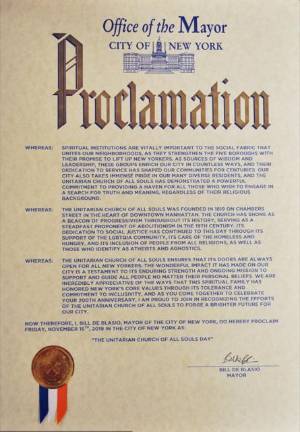

Mayor Bill de Blasio proclaimed Nov. 15th, 2019 as "The Unitarian Church of All Souls Day," praising its long tradition of promoting social justice, caring for the hungry and homeless, supporting the LGBTQIA community and "providing a haven for all those who wish to engage in a search for truth and meaning" - including atheists and agnostics.

In a recent sermon, Senior Minister Galen Guengerich described the church's founding in 1819 "as an open-minded revolt against a culture dominated by closed-minded religious orthodoxy," whose founders empathized reason rather than revelation and science over scripture.

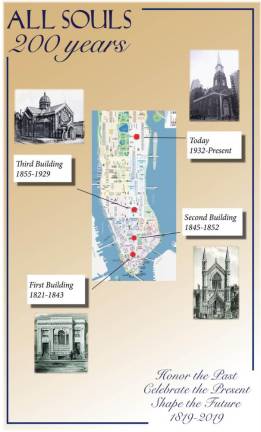

All Souls, as it is known, has had three different names and four different locations in its 200 years, steadily moving uptown along with the city's population. It settled at its current location, at 80th Street and Lexington Avenue, in 1932 and its nearly 90-year old Georgian sanctuary is now undergoing a major renovation. Its Christmas Eve services this year will be held at the nearby Temple Shaaray Tefila.

Undaunted by the construction, All Souls marked its Bicentennial with a three-day celebration with intimate dinners at congregants' homes, dessert and dancing at the church, old-fashioned games and historical performances. Susan Frederick-Gray, president of the Unitarian-Universalist Association, gave a special sermon. The church also published a 400-page coffee-table book, "All Souls at 200," tracing its rise from a small gathering in a downtown parlor to a flagship of Unitarian-Universalism.

A Liberal Religion

As the book recounts, Unitarianism was virtually unknown in New York City in 1819 when William Ellery Channing, a Unitarian minister in Boston, stopped at his sister's home on Broome Street on his way to Baltimore to speak at a friend's ordination. Lucy Channing Russel invited about 40 of her friends to hear her brother practice his upcoming sermon. As they listened raptly, Channing defined the principles of the liberal religion called Unitarianism, saying that the Bible should be interpreted through reason, not taken literally; that Jesus was a human to be followed, not a God to be worshipped and that God loves people of all faiths - a sharp contrast to the strict Calvinism of the day.

Channing's sermon caused an uproar in Baltimore. The text was distributed widely and some Christian clergy asked their congregations to pray for the Unitarians and their “sad delusions.” But others were drawn to the ideas Channing articulated and on his way back to Boston, New Yorkers were clamoring to hear him. Mrs. Russel's friends rented the largest hall they could find--at the College of Physicians and Surgeons on Barclay Street - and Channing spoke three times to overflow crowds. Sensing a hunger for liberal religion in New York, a group of 34 men, mostly college-educated merchants and lawyers, founded a small church at Broadway and Chambers streets to bring Unitarianism to the city permanently.

Disparaging remarks from more "orthodox" Christian churches began almost immediately. Rev. John Mason, minister of the Scotch Presbyterian Church on Murray Street, called the Unitarians “worse than the devil” and “enemies of our Lord Jesus Christ, and all that is valuable in his religion.”

By the 1830s, however, All Souls had attracted some of the New York's most enterprising citizens as members, including industrialist Peter Cooper; Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant, lithographer Nathaniel Currier, landscape architect Calvin Vaux and author Herman Melville.

In the coming years, All Souls members and its minister, Rev. Henry Whitney Bellows, played key roles in the creation of Central Park, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cooper Union, the ASPCA and the Union League Club. Cooper and Bryant also helped launch President Lincoln's presidential campaign when they invited the little-known lawyer from Illinois to speak at Cooper Union in 1860.

ALL SOULS AND THE CIVIL WAR

All Souls itself played a vital role in the Civil War, as described in this excerpt from "All Souls at 200:"

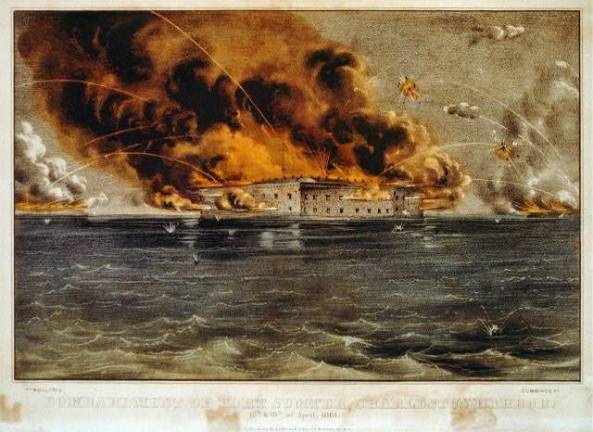

1861: Whispers of War

Slavery was causing bitter divides across the country. Even New Yorkers' loyalties were torn. The state had outlawed slavery in 1827 but New York City's banks financed the Southern slave economy; its merchants bought and sold vast quantities of cotton; its factories and sweatshops turned cotton into clothing and other goods and its ships and rails carried them all around the world.

New York City ministers who spoke out against slavery did so at their peril. When an interim minister at All Souls gave a pro-abolition sermon in 1837, several wealthy donors walked out and he was denied a permanent post.

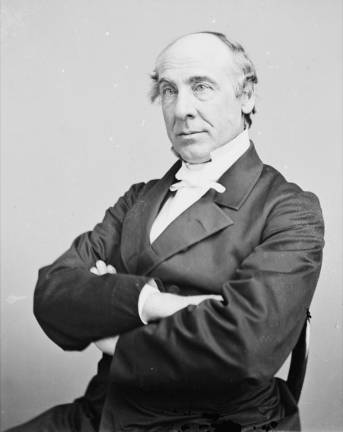

His successor, Rev. Bellows, had also been warned not to publicly condemn slavery, but he had seen it up close while working in the South and detested it. He also believed in supporting the Union even if it meant a bloody war that would divide his church as well as his country. He was saying as much in a sermon on Sunday morning, April 14, 1861, when whispers began rippling through the congregation.

It wasn't outrage against his sermon. The news had just reached New York that Confederate troops had fired on the U.S. Army at Fort Sumter in South Carolina two days earlier. "The congregation erupted with a surge of patriotism that echoed back with courage and confidence the sentiments I had almost feared to express, yet had not dared to stifle,” Bellows later wrote. At the end of his sermon, the assembled worshipers rose and joined the choir in spontaneously singing the national anthem.

The Women's Central Association of Relief

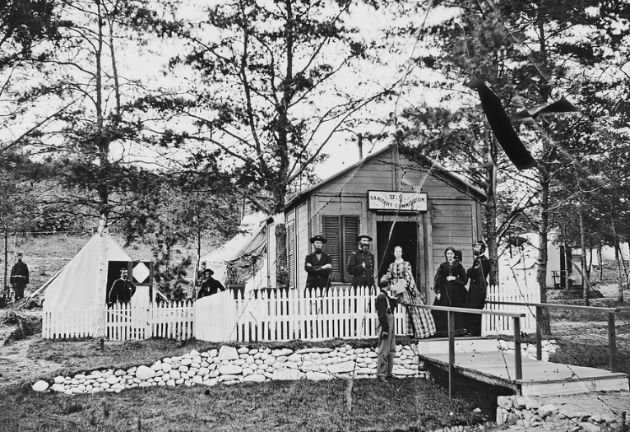

With the country rapidly mobilizing, many women were eager to help support the Union troops. Concerned about the sanitary conditions on Staten Island, where hundreds of volunteers had pitched tents on their way to Washington D.C., Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the nation’s first female physician, invited some of New York's most prominent society women - including several from All Souls - to form an aid association.

Word spread rapidly about the effort and by the following week, more than 4,000 women gathered at Cooper Union and formed the Women’s Central Association of Relief to collect food, clothing and medical supplies for Union soldiers and train nurses to work in military hospitals. The Women’s Central, as it was called, recruited women across the country to cook, serve and run kitchens in army camps, serve on hospital ships and operate lodges and rest stops for traveling and wounded soldiers. The Women's Central network would go on to contribute goods and services valued at over $1 billion in today's currency to the Union cause.

Although she was just 24 years old, All Souls member Louisa Lee Schuyler served as the association's corresponding secretary. Letters soon flooded into her office, often from soldiers’ mothers and wives, describing horrific conditions in the military camps: troops going without food for long periods, uniforms falling apart, diseases running rampant, wounded soldiers without bandages or painkillers and sick recruits piled into churches with no toilets or running water. The Women’s Central tried to pass the reports along to officials in Washington, but the War Department rebuffed their efforts and made no provisions to receive the nurses they trained.

The women prevailed on Rev. Bellows to lead a contingent of physicians to Washington and implore the government to address conditions in the camps. (According to some accounts, while on route, Bellows and the three male doctors decided that a “women’s association” wouldn’t hold much sway with army generals and created the more authoritative-sounding “U.S. Sanitary Commission” to oversee the operation.)

Bellows' group was well received, initially. He spoke privately with President Lincoln for half an hour. “If you had seen your humble husband haranguing the President ... you would have fancied him suddenly promoted into the office of premier,” he wrote to his wife, Eliza. But the War Department regarded the team “as weak enthusiasts, representing well-meaning but silly women,” he wrote.

They stayed in Washington for 20 days and grew increasingly frustrated with the War Department’s indifference and ineptitude. While Lincoln kept calling for new volunteers, Bellows and the physicians warned that half the soldiers already recruited would be dead of camp diseases in a few months if the army didn't take care of the sick and the wounded.

The U.S. Sanitary Commission

In June 1861, the War Department relented and appointed the U.S. Sanitary Commission to oversee the welfare of the army. Bellows was named president and over the next four years, he divided his time between the All Souls pulpit and military camps and battlefields. He and his fellow commissioners often slept on the ground under their overcoats and saw unspeakable carnage.

After each major battle, it fell to the Sanitary Commission to tend to the wounded, most of whom were simply left on the field. At Antietam, Bellows wrote, “nearly 10,000 of our own wounded, besides many of the enemies, were left, an immense proportion of the whole shelterless in the woods and field, without any adequate supply of surgeons, and with not a tenth part of needed medical stores.”

He arrived at Gettysburg three days after the battle in July 1863 and stayed for a week. He wrote to Eliza: “The suffering here with 70,000 wounded is unspeakable! ... I see no chance of getting back before Sunday. Have the pulpit supplied or have the church closed as you please ... Do not worry about me.”

Their services were severely tested when the Union Army attempted to capture the Confederate capital in Richmond, Va., and was badly routed. The Sanitary Commission vowed to evacuate 2,500 wounded soldiers from the Virginia Peninsula to New York in 30 days. They converted old boats into hospital and transport ships and sent a telegram to the Women's Central “calling for nurses & without delay.”

A group of All Souls women, including Eliza Bellows, made numerous round-trips on the hospital ships, caring for men with fever, dysentery and all too often, mortal wounds. Some brought their household servants along to help.

1863: The Metropolitan Fair

With no government funding to call upon, the U.S. Sanitary Commission depended on volunteer efforts to raise the money it needed. Cities around the country held elaborate expositions, dubbed "Sanitary Fairs," and competed to see which could bring in the most revenue. Chicago’s fair included a six-mile long parade of militiamen, politicians and farmers showing off cartloads of crops. The Philadelphia fair had nearly 100 booths selling all manner of curiosities, from war relics to Turkish divans for smokers.

Not to be outdone, women from All Souls and other New York churches organized an even larger "Metropolitan Fair" in 1863 that lasted 18 days and occupied much of what is now Union Square. It included a vast restaurant and displays of arms, trophies, jewelry, hats, sewing machines and other technical wonders, porcelain, saddlery and lingerie. Exhausted from months of preparation for a major display, All Souls member Caroline Kirkland died in her sleep, at age 63, two days after the fair opened. In all, the Metropolitan Fair raised over $1 million for the Sanitary Commission—the equivalent of about $30 million today.

One of the most popular exhibits was the gallery of fine art loaned by wealthy New Yorkers from their private collections. Bellows thought citizens might enjoy seeing such works on a permanent basis and took the idea to the Union League Club, a social club he helped establish to shore up support for the war. The Union League Club, in turn, rallied support for the idea from other civic leaders, artists, collectors and philanthropists, resulted in the founding of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1870.

First editions of All Souls at 200 can be purchased at the church at 1157 Lexington Avenue or at Shakespeare & Co., at 939 Lexington Avenue. Additional copies can be purchased on Amazon.com.