A Historical Walk Through Central Park — Before It Was A Park

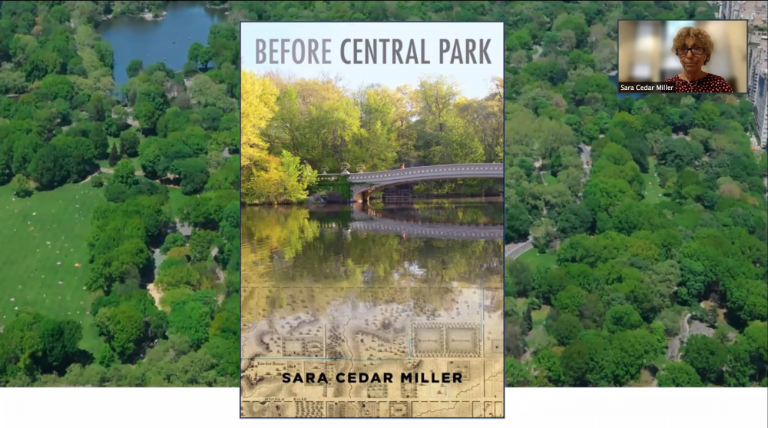

Sara Cedar Miller’s new book, “Before Central Park,” explores the geography’s history

Beloved as a destination for tourists and a refuge for city dwellers, Central Park has a “millennia” of history inhabited by humans and “eons” of existence as land, according to Sara Cedar Miller.

Miller, Central Park Conservancy’s historian emerita, drives that point home in her new book, “Before Central Park,” published on June 28. In some ways, it’s a culmination of her nearly four decades of work for the Conservancy, where she originally started as a photographer; Research for the book itself, she said, was a “seven year odyssey.”

In a book talk with local group Friends of the Upper East Side on Tuesday, Miller broke her findings down into three sections, as they also appear in “Before Central Park”: “topography,” “real estate” and “the idea of a park.” Some features of the past, like the untamed swampiness of some parts of the land that became Central Park and the canal that almost intercepted it, may feel unrecognizable to modern-day readers. Others, like the asset of location in relation to property value, remain all too familiar.

“Topography Is Destiny”

Perhaps among the park’s oldest remaining features, the boulders — used often as sunbathing perches in the summertime today — have their own tale. Called “glacial erratics,” Miller said, they were deposited where they stand now by a melting glacier some 11,000 years ago.

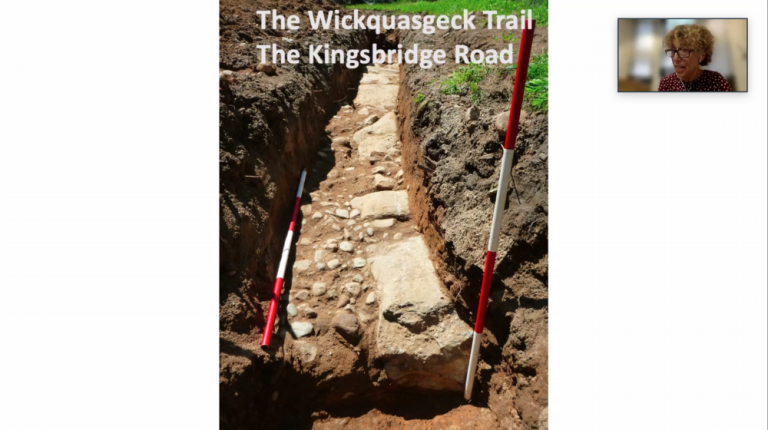

Eventually, the underlying land — before it was transformed into a park in the 1850’s — became the site of the convergence of Harlem, Bloomingdale and Yorkville, with winding paths and trails. Some, Miller explained, were forged by Lenape Native Americans and later went through multiple iterations and overseers, as in the case of the “Kingsbridge Road” (now marked along McGowan’s Pass), originally a Native American path that became a road for wagons and ultimately a toll-bearing highway overtaken by the English.

“Topography is destiny,” Miller said. In places where the land was too water-logged and unnavigable, appearing hazardous in photos, it was left largely untouched.

But in spots where it was beautiful and tame, it was used as a sanctuary. In 1797, a New Yorker named James Amory purchased a lot in what is now Central Park, after his family contracted Yellow Fever. Now recognized as the Central Park Mall, the Dene and parts of the East Green and east Sheep Meadow, Amory’s land offered isolation from the city — as the park did again for so many New Yorkers, more recently, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Later, in the 1820’s as a “canal craze” swept the nation after the success of the Erie Canal, the northeast corner of today’s Central Park almost got its own water feature. The canal through Harlem was never realized, but makes an appearance in Chapter 11 of “Before Central Park.”

Building Seneca Village

What was built, around the same time, was Seneca Village, “the largest Black property-owning community in New York and possibly the country,” Miller said. An almost 20-acre parcel of land, near the West 85th Street entrance to Central Park, was subdivided into 200 lots sold by John Whitehead — and sold “exclusively to members of the Black community,” according to Miller. Eventually, it became a residential community of predominantly Black landowners and Black, Irish and German renters.

“The most significant findings reveal vast numbers of property transfers during the life of the community, proof that real estate investment and capital gains were not exclusive to white New Yorkers,” Miller said. Later, she added of her discoveries, “I didn’t know Seneca Village people bought and sold real estate and made a profit — I just somehow had the idea that people gradually moved in and then they had to leave, but that’s far from the truth.”

After 1821, owning Seneca Village property also afforded some Black men the right to vote. And many owned properties Downtown, too. “They were leaders in New York’s social and political Black community,” Miller said.

One person in particular — Elizabeth Gloucester, known as one of the wealthiest Black women in the country — stood out. In 1856, when she received $460 from the city for one of her properties in Seneca Village, she turned around and purchased a cheaper lot near Fifth Avenue and East 98th Street, “knowing full well that it would prove to be an outstanding investment,” according to Miller.

“Location, Location, Location”

By that year, the city had begun purchasing the land to create Central Park, paying over $5 million for 59th through 106th Streets. “But the records that spelled out exactly how much each landowner received to release their property to the city seemed to be lost,” Miller said. With help from Aaron Goodwin, Miller’s “genealogist friend,” she uncovered a treasure trove of information.

“I plugged the property awards onto a grid and the results seemed to be consistent with the real estate mantra, ‘location, location, location,’ Miller said, explaining that lots “closest to the developing city, around 59th Street, received the largest awards, even though the land was some of the worst, rockiest, swampiest land in the area.” Identity of the landowners, like their race, nationality or socioeconomic status, didn’t impact the amount of money offered by the city, Miller found.

Her book is packed with stories — and yet she still plans to blog about all that didn’t make the final cut. “I have something like 65 topics that I feel like I didn’t touch on,” Miller said. To get up to speed, she suggested the Corner Bookstore, at the intersection of East 93rd Street and Madison Avenue, not far from the Central Park Reservoir, as a spot to pick up a copy of “Before Central Park.”

“The most significant findings reveal vast numbers of property transfers during the life of the [Seneca Village] community, proof that real estate investment and capital gains were not exclusive to white New Yorkers.” Sara Cedar Miller