The New York Scandal that Captivated America During the Gilded Age

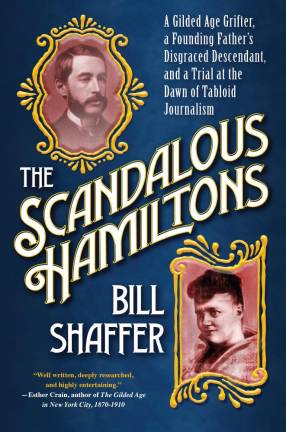

“The Scandalous Hamiltons,” a new book by Bill Shaffer, details the events that left the Hamilton family’s reputation in shreds

In 1889, Robert Ray Hamilton, the great-grandson of Alexander Hamilton, was looking to divorce the sex worker who had supposedly given birth to his daughter. Leading to a scandal that rocked the nation, the story was featured in daily newspapers of the time. It also is the focus of “The Scandalous Hamiltons,” a new book by Upper West Side author Bill Shaffer. “If it was a scandal that had happened today, by nighttime, there would have been satellite trucks lining the street,” Shaffer said.

While Hamilton came from a wealthy, well-regarded family, Hamilton’s wife, Evangeline Steele, lived in a whole other America. “Eva was born dirt born in the backwoods of Northeast Pennsylvania,” Shaffer said. Her father, a woodcutter who struggled with alcoholism, constantly moved his six children while looking for a job. “Eva didn’t have much of an education; she only went to school until the fourth or sixth grade,” Shaffer said.

The two met in a brothel in 1885, where Steele was working. “They formed a part-time, ‘I’ll see you when I’m in town’ kind of relationship,” Shaffer said. Looking to make the relationship permanent, Steele told Hamilton that she was pregnant with his child. Following the social customs of the time, the two married on January 7, 1889, in Paterson, New Jersey.

Shortly before the wedding, Steele visited her mother in Elmira, New York. It was common for women during that era to spend the last few months of their pregnancy on bedrest, often in a relative’s home, Shaffer said.

When Steele returned, she had produced a baby, one that wasn’t hers but was purchased from a baby farm. “Baby farms were illegal orphanages that a midwife might operate,” Shaffer said. If a woman gave birth to an unwanted child, and didn’t want to make the news public, she could give that baby to a midwife to be illegally sold.

Hamilton and Steele hired a baby nurse and temporarily moved to San Diego. Steele didn’t like the West Coast, and she and the nurse drank heavily. “In the summer of 1889, they returned to the East Coast to take up residence back in New York, but they stopped in Atlantic City for four weeks or so,” Shaffer said. “The day before they were set to leave, Ray asked Eva for a divorce.”

Steele Arrested

In the commotion that followed, Steele stabbed the baby nurse and was subsequently arrested. “By nightfall, reporters from New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, all through the area, had descended on Atlantic City,” Shaffer said. “Once that happened, Ray’s reputation was in tatters.”

Shaffer came across the story after moving back to the Upper West Side a few years ago. He had lived in New York City during the 1980s, when he met his wife. “We ended up getting married and buying a house in Connecticut where we raised our daughter,” Shaffer said. “In 2017, we were empty nesters, and we decided to return to the city.”

Two months later, when moving his parked car during the night, Shaffer stumbled upon the Hamilton Fountain, located on 76th Street and Riverside Drive. “I thought, this is a really beautiful fountain; this looks like something you would see at Grand Central terminal,” Shaffer said.

In his will, Ray Hamilton left $10,000 to the city of New York for the construction of a horse trough fountain, a spot for the horses who drew carriages around the city to refresh themselves. Wanting the black sheep of their family to be forgotten, Hamilton’s family delayed the project as long as they could. “Ray’s father died in 1904 and one month later, the city approved a site for the fountain,” Shaffer said.

The project was given to Warren and Wetmore, the architectural firm that had designed Grand Central and was set for the Upper West Side, as the area was only starting to be developed. “This location was obscure, and it was a location that members of the Hamilton family wouldn’t be walking past every day,” Shaffer said.

“I’m Going to Write It”

Shaffer discovered the story from an architectural point of view. “I do historical architectural research and design research for authors and design firms,” he said. Wondering why a prestigious firm designed a fountain on the Upper West Side, Shaffer started to research the story behind the trough. “I thought, surely there must be a book about this scandal somewhere. When I found there wasn’t one, I said, well, I’m going to write it then,” he said.

In researching the fountain, Shaffer uncovered how much the neighborhood had changed since Hamilton and Steele’s time. “Riverside Drive, in the late 1890s, early 1900s, was just being developed from sparsely populated lots,” he said.

When Central Park opened in 1858, apartment buildings sprung up around the area. “Once Riverside Park opened in 1873, there was hope from a lot of people that it would have that same cachet and prestige as living next to Central Park,” Shaffer said. In its early days, many single-family houses were built around the park, which were then replaced after around 20 years with elegant brownstones and apartment buildings, he said.

Shaffer uncovered the local, historical gossip through a happy accident, he said. “There was something about the architectural beauty of this fountain that I was just drawn to,” he said. “In fact, I tell people I didn’t really find the book, the book found me.”

“If it was a scandal that had happened today, by nighttime, there would have been satellite trucks lining the street.” Author Bill Shaffer