Hopper in the City

A new show at the Whitney is the first to examine the artist’s work through the lens of his hometown, New York

Edward Hopper (1882-1967) had an enduring love affair with New York, a place he called home for nearly six decades. He was the ultimate flâneur, a connoisseur of the city’s ordinary sights — rooftops, row houses, bridges, street corners, theaters and restaurants— which he portrayed in an extraordinary way, in an extraordinary light, featuring solitary figures or few figures or none at all.

A keen observer, he strolled the streets of the city, rode the El train and peered into apartments, offices and the automat, recording small, private moments like a woman gazing out of her window — a recurring motif — or other everyday scenes, like a waitress tending to a window display in a café, or a woman sitting at her sewing machine. The latter, “Girl at a Sewing Machine” (c. 1921), pictures a female figure facing a sunny window. The composition and the light echo Dutch genre painters like Vermeer, an artist Hopper clearly admired.

His subject was the quotidian, just ordinary stuff and ordinary people, which he captured in tight close-ups, as if he were wielding a camera and not a paintbrush or chalk.

He often let the architecture tell the story, because it was a mood he was going for — a certain urban vibe and quietude and tension that played out alongside the storied landmarks and flashy skyscrapers that were grabbing the headlines and transforming the city in the last century. He made an art out of depicting the horizontal landscape — brownstones and bridge spans — once joking, “I just never cared for the vertical.”

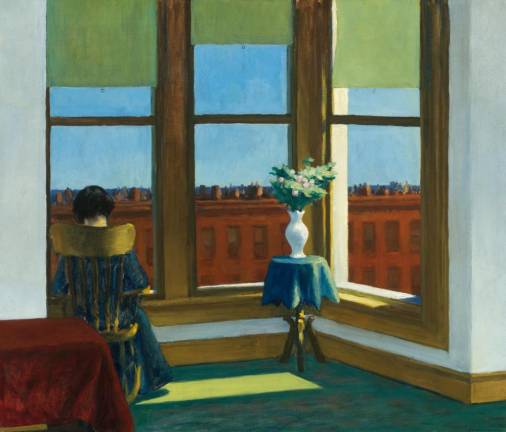

He liked infrastructure, the Manhattan Bridge, the Williamsburg Bridge, the Queensboro Bridge and Macomb’s Dam Bridge, which connects Manhattan to the Bronx. The Brooklyn Bridge? Not part of his repertoire. His wife, Josephine Verstille Nivison, a painter herself and frequent model for her husband’s works, explained that he excised the landmark from “Room in Brooklyn” (1932) because, though it was part of the view from the window, the painting would look cluttered if he included it. He had a vision, and he stuck to it.

This brilliant show, organized by drawings/prints curator Kim Conaty and senior curatorial assistant Melinda Lang, features some 200 items — a slew of iconic oil paintings, in addition to watercolors, prints, drawings and archival material — much of it drawn from the museum’s own substantial collection. It is being billed as the first to explore Hopper’s relationship to the city, the setting and central player in the vast majority of works presented.

Starting Point

Hopper was born in Nyack, across the Hudson, and moved here in 1908 after commuting to study at two art schools. He worked as a commercial illustrator at first, producing a wealth of cover art for trade journals and more that trained him for the career in fine art that he was destined for.

In 1913 he moved to Greenwich Village, where he occupied two different apartments on the top floor of a walkup at 3 Washington Square North (still there). He was joined by his wife Jo after their marriage in 1924 and stayed for more than 50 years.

He used the place as a starting point for explorations of the city, beginning with his immediate environs — his rooftop (“My Roof,” 1928) and the views from his window of Washington Square Park, Judson Memorial Church and the local architecture (“November, Washington Square,” c. 1932/1959; “Town Square [Washington Square and Judson Tower]),” 1932; “City Roofs,” 1932).

He was a realist, but his works were not always literal transcriptions. In his theater pieces, for instance, he mostly drew on memory and preparatory sketches of a variety of venues to forge composites of the interior architecture.

Ticket Stubs

He and Jo were theater nuts and saved and annotated their ticket stubs, exhibited here in a long, colorful row in a vitrine. But a night out at the theater was not just entertainment for the couple. For Hopper, the stage sets and the interiors of the houses were material that fed the art; for Jo, a former member of the Washington Square Players, the performances on stage were no doubt inspiration for the parts she was called on to play in her husband’s productions.

She posed for the pensive usher in one of Hopper’s famously mysterious works, “New York Movie” (1939). Only a sliver of the screen with its fantastic illusions can be discerned; the focus is off-screen, on the sidelines, where reality kicks in and a weary-looking usher, illuminated by a wall sconce, appears disengaged and lost in her thoughts.

The interior structural elements and appointments, cherry picked from four movie theaters, are as much a part of the drama as the people. They’re depicted with great specificity—note the curtain tie-backs and the detailing on the overhead lighting fixtures—making them very real on the one hand, but then again, part of the illusion you sign on for when you enter a movie theater.

So the painting fits in very nicely with one of the show’s central themes, the tension between reality and fantasy. The wall text states that Hopper wrote in his personal journal that he yearned to realize “a realistic art from which fantasy can grow.” Just imagine what that usher was thinking.